As the global rare earth supply chain fractures under U.S.–China tensions and escalating tariffs, a new geopolitical order is taking shape. China’s decades-long dominance faces its first real challenge, and India — with vast reserves, strategic partnerships, and new policy momentum — is emerging as a critical player in building a more diversified and resilient rare earth ecosystem. India has third largest reserves after China and Brazil but production is mere 0.5 percent at present which needs to be boosted to become a strategic player in reshaping the world’s rare earth future.

By Rohit Dhuliya

The world’s scramble for rare earth minerals — the unseen backbone of modern technology — has entered a decisive new phase. For decades, China has enjoyed an almost unassailable dominance over this critical sector, refining more than 80 percent of the world’s rare earth elements (REEs) that power everything from smartphones and wind turbines to electric vehicles and precision-guided missiles.

Now the global balance is shifting. A wave of trade tensions, resource nationalism, and new industrial strategies — led by the U.S. and its allies — is redrawing the contours of the rare earth map. And amid this high-stakes reshuffle, India is emerging not as a bystander, but as a potential game-changer.

China’s Strategic Grip: Monopoly by Design

China’s control over the rare earth supply chain is no historical accident. It was a deliberate, decades-long strategy — integrating upstream mining, midstream refining, and downstream manufacturing into one cohesive system. As early as the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping famously declared, “The Middle East has oil; China has rare earths.”

Beijing invested heavily in refining capacity while tolerating the severe environmental costs that drove competitors out of the market. Western nations, eager to outsource the “dirty” stages of production, surrendered the supply chain in exchange for cheaper materials. The result was a global dependency that gave China a unique geopolitical lever.

In recent years, that leverage has been exercised with increasing precision. China’s export controls on gallium, germanium, and certain rare earth magnets in 2023–24 were not just economic measures — they were geopolitical signals, directly aimed at the high-tech and defence industries of the U.S., Japan, and Europe. Beijing’s message was clear: those who seek to contain China’s technological rise will have to reckon with its mineral might.

America’s Tariff Wall: Protection or Provocation?

The United States, once a producer of rare earths, ceded its edge when environmental and cost pressures shuttered domestic mines. Today, Washington is racing to rebuild its critical mineral supply chain under the twin banners of national security and economic resilience.

The Biden administration’s tariff escalation on Chinese goods — particularly in high-tech and green manufacturing sectors — is part of this broader effort to decouple from Beijing’s mineral ecosystem. The 2024 round of tariffs, covering electric vehicles, semiconductors, and critical minerals, was less about revenue and more about leverage — a strategic nudge for American and allied firms to diversify supply chains away from China.

Yet tariffs alone cannot undo three decades of structural dependency. While they may protect nascent U.S. producers and catalyse domestic investment, they also risk short-term inflation in clean-energy technologies and consumer electronics. For the global South — including India — these trade walls create both opportunity and complexity: the chance to step into new supply roles, but within a fractured, high-friction global marketplace.

A Fragmented Future: From Unipolar to Multipolar Supply Chains

What we are witnessing is the disintegration of a unipolar system into a politically fragmented, multipolar one. The new rare earth order will be less efficient, more expensive, and more politically charged. Instead of a single, China-centred chain, we are likely to see three overlapping systems:

- A China-led bloc, supplying much of the Global South and partners aligned through initiatives like the Belt and Road;

- A U.S.-led ecosystem, anchored in North America, Australia, and select allies; and

- An emerging independent cluster, where countries like India, Vietnam, and Brazil position themselves as neutral diversification hubs.

This fragmentation may raise costs in the short term, but it will enhance resilience and reduce systemic risk. For energy security, defence readiness, and industrial autonomy, that trade-off is increasingly acceptable.

India’s Moment: From Potential to Power

India sits at a remarkable juncture in this geopolitical drama. Geologically, it holds one of the world’s largest reserves of monazite and other rare earth-bearing minerals, concentrated along its coasts and river basins. Politically, it enjoys the trust of both Western democracies and developing nations. Economically, it is one of the fastest-growing markets for renewable energy, EVs, and digital infrastructure — all heavy consumers of REEs.

New Delhi has finally recognised this convergence of factors. The inclusion of rare earths in the Critical Minerals List, the launch of offshore exploration bids, and the planned creation of a dedicated critical minerals mission are strong signals that India is moving from rhetoric to execution.

But the challenge lies not in policy intent, but in operational delivery. Mining is only the first step; the real value lies in refining and magnet manufacturing, where China remains dominant. India must therefore attract private capital and global technology partners to build an integrated, end-to-end supply chain — from extraction to component fabrication.

The Three Pillars of India’s Strategy

For India to move from the sidelines to the centre of global rare earths, it needs to act with urgency and precision on three fronts:

- Capital and Private Sector Participation:

Public auctions alone will not build an industry. India needs a financial ecosystem that blends public risk guarantees, tax incentives, and private equity participation to make projects viable. - Technology Partnerships:

Building refining and separation capacity requires advanced know-how. India should forge long-term technology alliances with Japan, Australia, the U.S., and the EU — not just for mining, but for downstream processing and recycling. - Sustainability and Environmental Governance:

China’s rise came at a heavy ecological cost. India must prove that growth and sustainability can coexist — through strict environmental standards, transparent licensing, and circular-economy principles.

If these pillars align, India could not only secure its own energy and industrial future but also emerge as a trusted diversification hub for the democratic world’s supply chains.

The Stakes: Technology, Power, and the Future of Globalization

Rare earths are not just another commodity; they are the lifeblood of the digital and green revolutions. Control over their production confers influence over the technologies that will define the 21st century — from artificial intelligence and quantum computing to electric mobility and renewable power.

The current U.S.-China confrontation, underpinned by tariff barriers and resource nationalism, is not merely about trade. It is about control of the materials that will shape the future balance of power. In this great reshuffling, India’s decisions in the next five years will matter profoundly.

If it acts boldly — mobilizing its geological wealth, policy momentum, and diplomatic leverage — India can become a pillar of a more diversified, resilient, and ethical global rare earth economy. If it hesitates, it risks watching the opportunity slip back into the orbit of established powers.

Conclusion: From Opportunity to Responsibility

The global rare earth transition is not only an economic opportunity but a test of strategic maturity. The unipolar era of Chinese dominance is giving way to a contested multipolar structure shaped by tariffs, alliances, and technological nationalism.

India’s challenge is to move quickly — but wisely — balancing growth with sustainability, and partnership with independence. In doing so, it can not only secure its own technological sovereignty but also contribute to a more stable and equitable global supply chain.

The race for rare earths is, in essence, a race for the future — and India has finally joined the starting line.

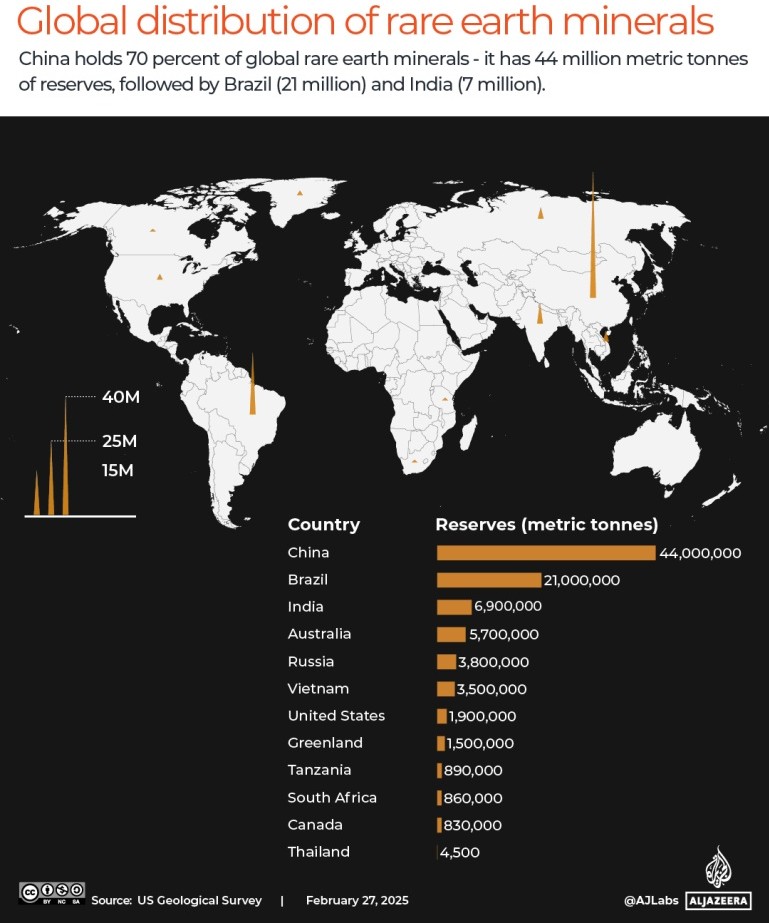

Based on the global reserves and production data, here are seven key countries that possess significant rare earth mineral deposits, moving from the largest holder downwards.

China: The dominant global leader. It possesses the largest known reserves and is by far the world’s top producer. Major mining sites include the massive Bayan Obo deposit in Inner Mongolia and ion adsorption clay deposits in the south.

Vietnam: Holds the world’s second-largest rare earth reserves. While its production has been historically modest, it is rapidly scaling up its mining and processing capabilities, partly in response to global demand for supply chains outside of China.

Russia: Has substantial reserves, ranking among the top globally. Key deposits include the Tomtor project in Siberia. Russia has the potential to be a major player, though its integration into Western supply chains is limited by geopolitical factors.

Brazil: Possesses significant reserves and is a noted producer. Its reserves are a critical part of the global picture outside of China.

India: India has the third-largest reserves in the world, primarily in the form of beach sand minerals (monazite) containing rare earths. It is now focusing on leveraging these resources to break into the global supply chain.

United States: Holds considerable reserves and has the world’s largest single rare earth mine outside of China at Mountain Pass, California. The U.S. is actively working to rebuild a complete domestic supply chain from mine to magnet.

Australia: An important and growing player. While its reserves are smaller than the countries above, it is a major producer and home to promising projects like the Mount Weld mine, which is one of the highest-grade rare earth deposits globally. It is a key partner in efforts to diversify supply.

Other Notable Mentions:

Myanmar: Has become a significant, though controversial, source of heavy rare earths, with much of its material being shipped to China for processing.

Greenland: Has vast potential for rare earth deposits and is a focus of intense geopolitical interest for future development.

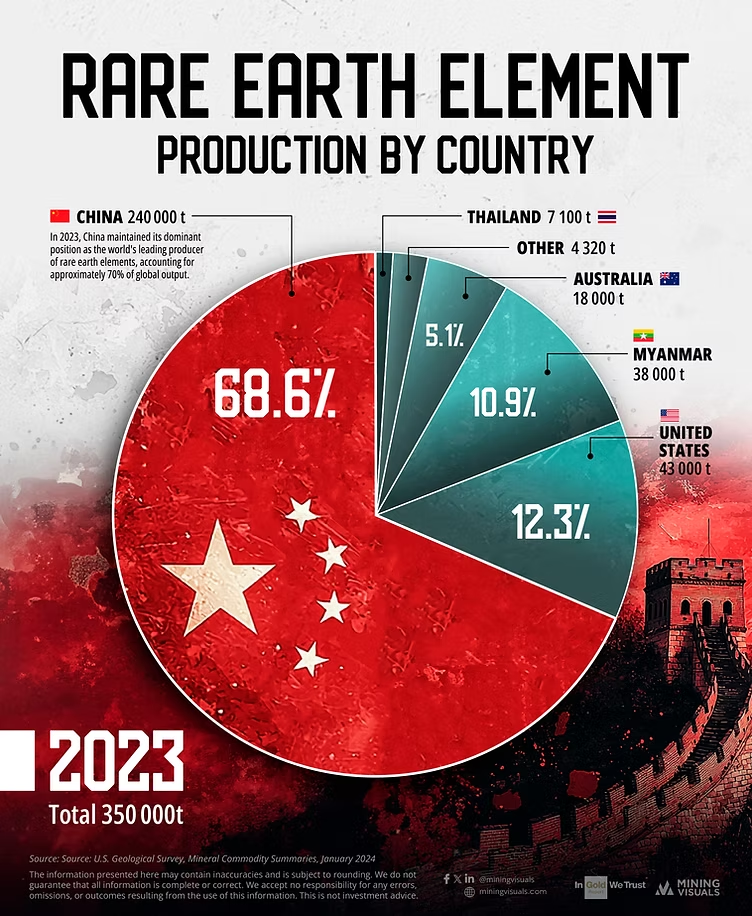

Top 7 Countries in Terms of Production

China: 68.6%

United States: 12.3%.

Myanmar: 10.9%.

Australia: 5.17 %.

Thailand: 0.6%

India: 0.5%

Russia: 0.5%

References

- U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Mineral Commodity Summaries: Rare Earths (2025).

https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center

→ Annual global data on production, reserves, and trade flows of rare earth elements. - OECD (2024). Critical Raw Materials for the Green Transition: Global Supply Chain Risks and Policy Responses.

https://www.oecd.org/environment/

→ Analysis of supply chain vulnerabilities and policy responses to resource dependencies. - The White House (2024). Executive Order on Securing Critical Supply Chains.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/

→ U.S. policy framework linking tariffs, national security, and rare earth diversification efforts. - China Geological Survey (2023). Rare Earth Resources and Industrial Development in China.

http://en.cgs.gov.cn/

→ Overview of China’s rare earth dominance, production capacities, and export policies. - Ministry of Mines, Government of India (2024). India’s Critical Minerals Strategy 2047.

https://mines.gov.in/

→ India’s policy roadmap for exploration, extraction, and value-chain integration of critical minerals. - International Energy Agency (IEA, 2024). The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions.

https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions

→ Data-driven insights on global demand for rare earths in the renewable and EV sectors.

About the Author

The author is a filmmaker, media critic, and commentator on global politics. Watch his films on YouTube to explore his thought-provoking work firsthand.