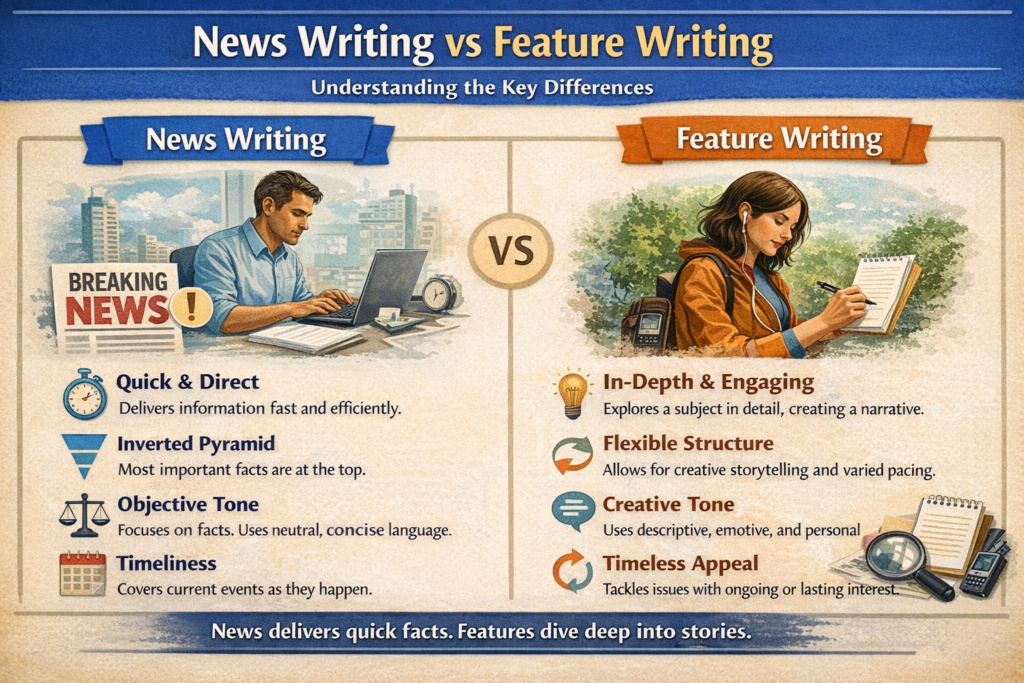

News reports tell readers what happened—quickly, clearly, and efficiently. Feature writing, by contrast, tells readers why it matters, how it feels, and what it means over time. Understanding the difference is essential for any journalist who wants to move beyond facts into storytelling.

By Subhash Dhuliya

News Writing: Speed, Structure, and Skimming

News stories are designed to be read fast. Their primary purpose is to convey information as efficiently as possible, often to readers who may only skim headlines and opening paragraphs. The traditional inverted pyramid structure places the most important facts at the very top, followed by supporting details in descending order of importance.

This structure suits the realities of news consumption. Readers dip in and out of newspapers, websites, and apps, often reading only a fraction of what is published. Editors, too, need stories that can be cut from the bottom without losing essential meaning.

Crucially, length alone does not transform news into a feature. Adding more facts, background, or quotes to a news story does not automatically give it depth or narrative power. A longer news article is still news unless its structure, purpose, and style fundamentally change.

Feature Writing: Meaning, Narrative, and Design

Features operate on a different plane. A feature story is not constrained by rigid structure or chronological order. Instead, it allows the writer to shape material deliberately, choosing where to begin, how to progress, and how to end.

The challenge of feature writing lies not in gathering information—often the same reporting skills apply—but in planning the journey of the story. Before writing a single paragraph, the feature writer must know:

- What the story is really about

- What theme runs through it

- How the reader will be drawn in and carried through to the end

A feature must be designed, not merely assembled.

Understanding the Brief: Your First Obligation

In most professional newsrooms, feature writers do not choose topics at random. They are commissioned by a Features Editor, who outlines expectations about length, tone, angle, and often suggests interviewees. This instruction is known as the brief.

The brief is not a suggestion—it is a contract. Writers should:

- Write the brief down

- Ask questions if anything is unclear

- Revisit it during research and before writing

If major new information emerges during reporting, the editor should be informed immediately. The brief may need to be revised. Writers who ignore this process risk producing work that is beautifully written—but unusable.

Many promising features fail because writers fall in love with the material they uncovered rather than the story they were asked to tell.

Knowing Your Market: Writing for Real Readers

Every publication has a target market—a defined group of readers with shared expectations about tone, values, and style. Some newspapers favour light, conversational features; others prefer analytical, restrained storytelling.

Readers tend to choose publications that reflect their worldview. Feature writers must therefore adapt their style to:

- The publication’s voice

- The expectations of its audience

- The cultural and social context of its readers

One of the best ways to understand this is to read features written by experienced colleagues in the same publication.

Beginning, Middle, and End: Planning the Whole Story

A feature must have a beginning, middle, and end, but these elements cannot be conceived in isolation. The entire structure needs to be mapped out in advance.

Many features average around 1,000 words, though length may vary. Some writers can plan mentally; most benefit from notes or outlines.

One helpful metaphor is to think of the feature as a circle. Wherever you choose to enter the story, you must complete the journey and bring the reader back to a satisfying conclusion. There is no single formula—but there must be coherence.

Where Do You Start? Choosing an Opening

Facing pages of notes and interview transcripts can feel overwhelming. The good news is that features have no “correct” opening.

Unlike news stories—where the lead must prioritise the most important fact—features allow multiple entry points. Scene-setting, reflection, character moments, or even jumping forward or backward in time are all valid.

Consider a shipwreck:

- A news lead must focus on loss of life

- A feature might open with wreckage on a beach

- Or with sailors saying goodbye weeks earlier

Each approach is legitimate if it serves the theme.

Feature introductions often emerge naturally from re-reading interview notes and research. What stayed with you? What image, moment, or revelation captures the essence of the story?

Structure and Theme: Holding the Feature Together

After the introduction, every paragraph must earn its place. Ask yourself:

- Why am I telling this now?

- Does this deepen the reader’s understanding?

- Does it move the story forward?

A strong feature has a clear, identifiable theme. Each paragraph layers information, emotion, or insight that builds toward a conclusion. Mixing multiple themes leads to confusion and weak endings.

Example: Choosing the Right Focus

A woman becomes the first in her family to attend university. Her story includes poverty, family history, a mentor teacher, and a plan to sponsor another child’s education.

Rather than telling her life story chronologically, a feature might open with her first pay cheque and the memorial fund she plans to create—then circle back to explain why.

This is not disorder; it is deliberate design.

Flow Matters: Linking Paragraphs Smoothly

Features should flow naturally from one paragraph to the next. Abrupt shifts in subject or poorly linked sentences break immersion.

Simple sentence construction and careful use of linking words (“but,” “however,” “meanwhile”) help maintain momentum. Always check that pronouns clearly refer to the correct subject.

A good test is to read the feature aloud. If the rhythm stumbles, the reader will stumble too.

Anecdotes: Small Stories with Big Impact

Anecdotes are short, self-contained stories that illustrate a point. Used well, they:

- Humanise abstract ideas

- Change pace and tone

- Create emotional connection

A businessman saved by a stray dog tells us more about luck, gratitude, and character than a paragraph of statistics ever could.

The caution: use anecdotes sparingly. Too many can clutter the narrative and distract from the central theme.

Quotes: Giving the Story a Voice

Features without quotes often feel flat. Direct speech introduces rhythm, emotion, and authenticity.

Choose quotes that reveal:

- Emotion

- Personality

- Conflict

- Unusual insight

Avoid quoting material that is purely factual. Facts can be paraphrased. Quotes should add something only the speaker can provide.

Reported Speech and Context

Reported speech helps:

- Save space

- Smooth transitions

- Introduce quotes naturally

Always ensure quotes remain in context. Selective quoting that distorts meaning damages credibility and invites complaints—from sources and readers alike.

Keep quotes from each interviewee grouped together to avoid confusion.

Language and Precision: Saying More with Less

Strong feature writing relies on precision, not ornamentation. Avoid:

- Excessive adjectives

- Obscure vocabulary

- Overly long sentences

Short, clear words usually work best. Read your copy aloud. If it sounds strained, rewrite it.

The Dangerous Little Word: “I”

The word “I” rarely belongs in features unless the piece is explicitly first-person (travel writing, “living the news” features). Overuse of “I” shifts focus from subject to writer.

In the best features, the writer is invisible.

Developing Style: Craft, Not Ego

Style cannot be taught in a formula, but it can be developed. Read widely. Analyse writing you admire. Ask colleagues for criticism—and accept it.

If your publication has a stylebook, follow it. Consistency builds credibility and makes editors your allies.

Above all, practise. Style emerges from discipline, not imitation.

From Information to Insight

Headline: Beyond Facts — Why Feature Writing Demands a Different Mindset

News writing prioritises speed, structure, and immediacy. Feature writing prioritises meaning, narrative, and connection. A feature is not a longer news story; it is a different form altogether—one that requires planning, sensitivity to audience, and respect for language. When done well, features do more than inform. They linger, resonate, and remind readers why stories matter.

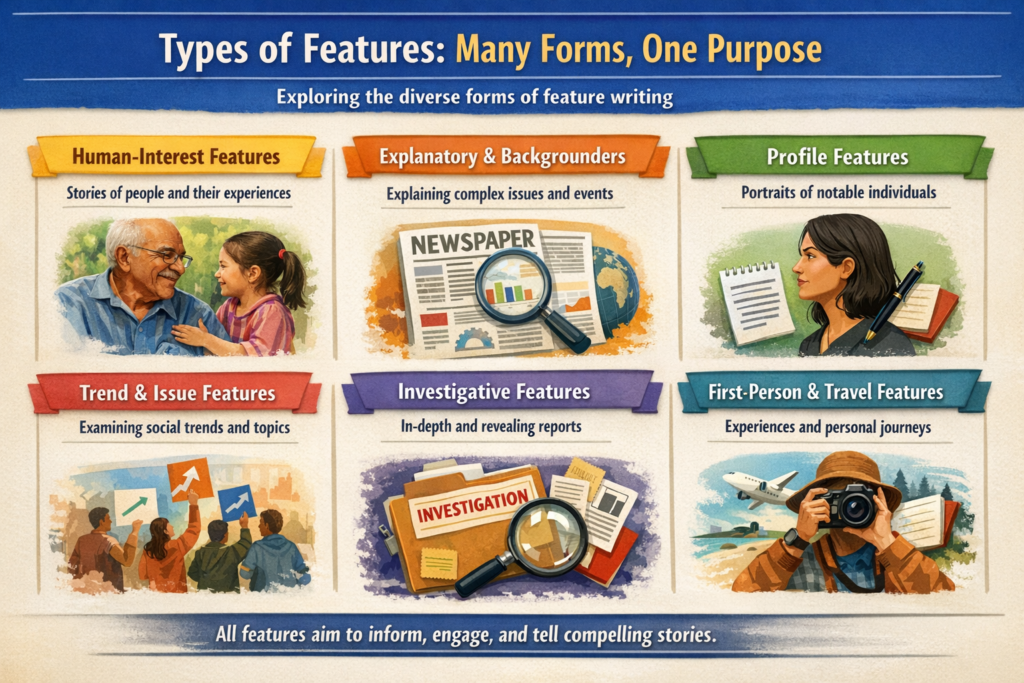

Types of Features: Many Forms, One Purpose

Feature writing appears in many forms, each serving a distinct editorial purpose while sharing a common goal: to deepen understanding and engage readers beyond the immediacy of news.

Human-interest features focus on individual lives to reflect broader social realities; backgrounders and explanatory features provide context and meaning to complex events; profiles explore personalities, motivations, and contradictions.

Trend and issue-based features examine emerging patterns shaping society; investigative features combine narrative with rigorous reporting.

First-person or “living-the-news” features draw on the writer’s direct experience to illuminate unfamiliar worlds.

Travel, culture, lifestyle, and narrative long-reads further expand the form. Despite their diversity, all successful features rely on the same fundamentals—clear purpose, strong structure, precise language, and storytelling that connects facts with human experience.

About the Author, Founder-Director, Newswriters.in, Former Vice Chancellor, Uttarakhand Open University & Former Professor, IGNOU | IIMC | CURAJ and Distinguished Professor & Dean, School of Creative Art, Design & Media Studies, Sharda University

1 Comment

Excellent