The war of ideas did not end in triumph; it ended in exhaustion. Grand ideologies that once promised equality, liberation, or national destiny have steadily lost their power to inspire trust or demand sacrifice. In their place has emerged a post-ideological world driven less by conviction than by convenience—where identity, emotion, and immediate outcomes matter more than coherent visions of the future.

Politics today is no longer anchored in competing philosophies of how society should be organized, but in managing perceptions, mobilizing sentiments, and delivering short-term results. While this shift has reduced the grip of rigid dogma, it has also created a troubling vacuum: a public sphere rich in noise but poor in shared meaning, where narratives replace ideas and power survives without moral certainty.

By Subhash Dhuliya

Executive Summary: The War of Ideas Is Over: Entering the Post-Ideological Era

The article argues that the early 21st century—now in January 2026—marks the transition to a post-ideological era, in which the grand, totalizing ideologies that dominated modern history (communism, fascism, liberalism, religious fundamentalism, etc.) have lost their capacity to command deep, long-term loyalty and to provide universal narratives for political and social action.

Historical context and decline of ideology The 20th century was defined by fierce “wars of ideas” that mobilized societies, inspired revolutions, and justified global conflicts. However, repeated catastrophes—world wars, genocides, economic collapses, authoritarian failures, and the symbolic collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991—produced widespread ideological fatigue. Even the once-triumphant liberal democratic model now faces deep skepticism amid inequality, institutional dysfunction, and unresolved global crises (climate, pandemics, technological disruption). People have grown weary of rigid doctrines that promise moral certainty and utopian futures but repeatedly fail to deliver equitable, sustainable outcomes.

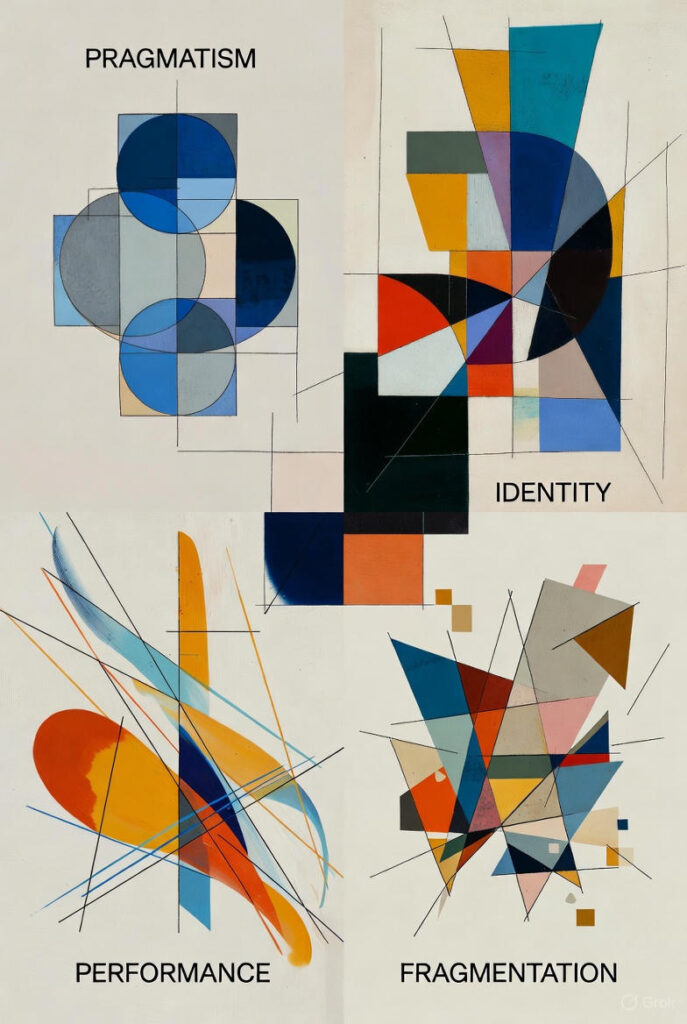

Core characteristics of the post-ideological era

- Pragmatism over doctrine — Leaders and societies prioritize “what works” (efficiency, results, short-term gains) over ideological purity. Policies routinely blend formerly incompatible elements (welfare + markets, nationalism + globalization).

- Fragmentation of belief systems — Individuals construct modular, hybrid worldviews from diverse sources rather than adhering to monolithic ideologies.

- Identity superseding ideology — Political mobilization increasingly organizes around ethnicity, religion, gender, region, culture, and lived experience rather than abstract theory. This heightens emotional intensity but fragments universal narratives and fosters grievance-based tribalism.

- Performance-based legitimacy — Authority derives from tangible outcomes (economic growth, security, crisis management) rather than philosophical or doctrinal justification.

- Shortened time horizons — Long-term utopian visions have been replaced by risk management, incremental fixes, and immediate-threat mitigation.

- Narrative and emotional politics — Digital media favors simple, resonant stories, outrage, symbolism, and spectacle over ideological depth. Truth often yields to emotional impact.

- Blurring of left–right divides — Traditional ideological boundaries have eroded; situational, context-driven coalitions dominate.

- Technological rationality as new authority — Algorithms, data, and expert systems increasingly legitimize decisions, often masking underlying value choices.

Is ideology truly gone? No. Ideologies persist in weakened, hybrid, or disguised forms and can resurface during crises. The absence of strong ideological anchors does not guarantee peace; it can produce confusion, polarization, elite manipulation, cynicism, and openings for authoritarianism or nihilism. Some argue that capitalism itself has become the unspoken, naturalized ideology of the age.

Repeated historical catastrophes eroded faith in grand ideologies. World wars shattered beliefs in progress, fascism culminated in genocide and nuclear devastation, and the Cold War prolonged conflict without delivering lasting peace. Economic crises further deepened disillusionment, producing ideological fatigue and paving the way for today’s pragmatic, fragmented, performance-driven politics

Has ideology really ceased to govern politics, or does it still exist in new, subtler forms? Has it been replaced by pragmatism, or has mistrust toward ideology given way to the primacy of identity? For much of the modern world’s political and intellectual history, societies were shaped by what can broadly be described as a war of ideas. Competing ideologies—liberalism, socialism, communism, fascism, nationalism, religious fundamentalism—did not merely coexist; they actively sought dominance, clashing in epic struggles that defined eras.

These belief systems offered comprehensive explanations of history, society, economics, and human purpose, serving as blueprints for the future. They mobilized masses, structured political parties, inspired revolutions, and justified wars, from the French Revolution’s libertarian ideals to the ideological fervor of the World Wars and the Cold War’s bipolar standoff between capitalism and communism.

Yet, as we navigate the early twenty-first century—now in January 2026—a profound transformation appears to be underway. While ideologies have not disappeared entirely, their capacity to command deep loyalty, long-term commitment, and universal narratives has sharply declined. The contemporary world increasingly operates in what can be described as a post-ideological era—a period marked not by grand doctrinal battles, but by pragmatism, fragmentation, identity fluidity, and issue-based politics.

This shift does not suggest the end of conflict or debate; far from it. Rather, it signals a change in how conflicts are framed, justified, and pursued. The era of ideological certainty, with its rigid dogmas and messianic promises, has given way to an age of provisional truths, tactical alliances, and narrative flexibility, where adaptability trumps orthodoxy.

This transformation did not occur overnight; it is the cumulative result of decades of disillusionment. Many of the twentieth century’s ideological experiments ended in excess, failure, or catastrophe, eroding faith in grand doctrines—a skepticism that has only intensified in the digital age

As global challenges like climate change, pandemics, and economic inequality persist, people turn less to sweeping theories and more to practical solutions. But what does this mean for governance, society, and individual agency? In exploring this post-ideological landscape, we must examine its origins, characteristics, and implications, recognizing that while the war of ideas may be waning, the quest for meaning endures in fragmented, often chaotic forms.

From Ideological Wars to Ideological Fatigue

The twentieth century was defined by ideologies that promised total answers to humanity’s woes. Communism, as articulated by Marx and Lenin, claimed scientific inevitability, positing history as a dialectical march toward a classless society. Liberal democracy, championed by thinkers like John Locke and later Francis Fukuyama, promised freedom, prosperity, and the “end of history” through market-driven progress. Fascism, under figures like Mussolini and Hitler, promised national rebirth through authoritarian unity and racial purity. Religious ideologies, from Islamic fundamentalism to Christian evangelism, promised moral order and divine salvation.

These systems were internally coherent, future-oriented, and deeply moralistic, dividing the world into clear binaries: right and wrong, believer and enemy, progressive and reactionary. They fueled monumental events—the Bolshevik Revolution, the rise of Nazi Germany, the decolonization movements in Asia and Africa, and the proxy wars of the Cold War era.

The twentieth century was dominated by ideologies that claimed total answers to human problems. Communism promised equality through historical inevitability, liberal democracy pledged freedom and prosperity, fascism sought national rebirth through authoritarian unity, and religious ideologies asserted moral order—together defining an age of ideological certainty and conflict

The repeated historical experiences have eroded public faith in such totalizing doctrines. The world wars unleashed unprecedented destruction, with fascism’s aggressive nationalism leading to the Holocaust and atomic bombings. The genocides in Rwanda and Cambodia exposed the dark underbelly of ideological purity. Economic collapses, like the Great Depression and the 2008 financial crisis, shattered faith in unregulated capitalism, while the Soviet Union’s implosion in 1991 was not merely a geopolitical event; it was a symbolic rupture that weakened the credibility of ideology as an infallible destiny.

Even liberal democracy, once heralded as triumphant, now faces widespread skepticism amid rising inequality, populist uprisings, and institutional gridlock. The COVID-19 pandemic of the early 2020s further accelerated this disillusionment, as ideological divides over lockdowns, vaccines, and economic aid gave way to pragmatic, data-driven responses in many nations, revealing the limitations of dogmatic approaches.

Environmental crises, too, have contributed to this fatigue. The failure of grand ideological solutions to address climate change—whether socialist central planning or capitalist innovation—has left societies grappling with incremental, often contradictory policies. The result is ideological fatigue: a collective weariness with rigid belief systems that claim moral superiority but fail to deliver equitable outcomes. People no longer see ideologies as saviors but as relics of a more naive era, prone to hubris and unintended consequences. This fatigue is evident in voter apathy, the decline of traditional party memberships, and the rise of independent or “swing” voters who prioritize results over rhetoric.

Defining the Post-Ideological Era

A post-ideological era does not imply the complete absence of beliefs or values. Instead, it reflects the decline of grand, universal ideologies as the primary drivers of political and social action. In this era, ideologies no longer monopolize political identity, and citizens are less willing to sacrifice materially or morally for abstract doctrines. Political legitimacy depends more on performance than philosophy, and narratives are flexible, selective, and often contradictory, allowing for rapid shifts in allegiance.

One of the defining features of the post-ideological era is the triumph of pragmatism over doctrine. Governments, corporations, and even activist movements now prioritize “what works” over ideological purity, favoring flexibility, performance, and immediate outcomes

This post-ideological condition is shaped by several interlocking forces. Globalization has blurred national boundaries, exposing people to diverse worldviews and undermining the insularity that once sustained ideological purity. Digital media, with its algorithms and echo chambers, has fragmented discourse, turning ideology into bite-sized memes rather than comprehensive treatises. Consumer culture promotes individualism and instant gratification, eroding the patience required for long-term ideological commitment.

Technological acceleration, from AI to biotechnology, outpaces traditional ideologies, rendering them obsolete in addressing novel ethical dilemmas. Finally, the fragmentation of authority—through the decline of religious institutions, traditional media, and nation-states—has democratized belief, but at the cost of coherence.

In this environment, politics becomes a mosaic rather than a monolith. Individuals draw from multiple sources to form hybrid views, unburdened by the need for consistency. This era’s hallmark is not apathy but a pragmatic eclecticism, where ideas are tools rather than truths.

Key Features of the Post-Ideological Era

One of the defining features of the post-ideological era is the dominance of pragmatism over doctrine. Governments, corporations, and even activist movements increasingly prioritize “what works” over what is ideologically pure. Policy decisions are framed in terms of efficiency, growth, security, and immediate outcomes rather than moral or philosophical coherence.

For instance, in the United States, bipartisan infrastructure bills in the 2020s combined progressive spending with conservative fiscal tweaks, eschewing ideological battles for tangible results like repaired bridges and expanded broadband. Similarly, China’s “socialism with Chinese characteristics” has long blended state control with market reforms, prioritizing economic growth over Marxist orthodoxy.

Political leaders frequently borrow ideas across ideological boundaries—embracing welfare schemes alongside market reforms, or nationalism alongside globalization—without feeling the need to reconcile contradictions. Ideological consistency is no longer a virtue; adaptability is, as seen in leaders like Emmanuel Macron in France, who positioned himself as “neither left nor right” to appeal to a weary electorate.

This pragmatism extends to international relations, where alliances form based on mutual interests rather than shared ideologies. The QUAD partnership between the US, India, Japan, and Australia focuses on countering China’s influence through practical cooperation on trade and security, not a unified democratic creed. Even in activism, movements like Fridays for Future emphasize actionable climate policies over theoretical debates about capitalism versus socialism.

In the post-ideological era, identity often outweighs ideology. Political mobilization is increasingly shaped by ethnicity, religion, language, gender, region, and cultural belonging, displacing coherent political theory as the primary source of alignment and conflict

Another key feature is the fragmentation of belief systems. Unlike earlier eras dominated by a few large ideologies, today’s belief landscape is highly fragmented. Individuals assemble their worldviews from diverse sources: identity politics, environmentalism, technological optimism, cultural conservatism, and personal experience.

This “pick-and-choose” approach reflects a broader cultural shift toward customization, akin to how streaming services allow users to curate playlists. Just as consumers personalize media feeds and lifestyles, political and moral identities are increasingly modular rather than monolithic. Social media platforms amplify this, enabling users to follow influencers who mix libertarian economics with social justice advocacy, or environmentalism with spiritual wellness. The result is a kaleidoscope of micro-ideologies, from eco-fascism to transhumanism, none of which achieve the mass dominance of past doctrines.

In the post-ideological era, identity often matters more than ideology. Politics is increasingly organized around ethnicity, religion, language, gender, region, and cultural belonging rather than coherent political theory. While ideology once claimed to transcend identity—think of communism’s international proletariat—contemporary movements often root legitimacy in lived experience and group identity.

The Black Lives Matter movement, for example, drew power from racial grievances rather than a singular economic ideology, inspiring global protests focused on representation and justice. Similarly, #MeToo harnessed gender identity to challenge power structures, bypassing traditional feminist theory for personal narratives. In Europe, regional identities fuel separatist movements in Catalonia or Scotland, while religious identities drive politics in India and the Middle East.

This shift has intensified emotional engagement but reduced the possibility of universal narratives. Politics becomes less about shared futures and more about recognition, representation, and grievance, leading to tribalism that can exacerbate divisions.

The post-ideological era is the abandonment of long-term utopian visions that once defined classic ideologies. Marxism promised a classless society, fascism eternal national rebirth, liberalism endless progress through freedom and markets, and religious fundamentalisms moral or divine salvation. These grand, future-oriented narratives gave people purpose and direction. Today, such sweeping promises have lost credibility

Performance-based legitimacy further characterizes this era. Earlier ideological systems justified authority through doctrine—divine right for monarchies, revolutionary theory for communists, constitutional philosophy for liberals. Today, legitimacy is largely performance-based. Citizens judge institutions by tangible outcomes: economic growth, service delivery, security, and crisis management. Electoral success increasingly depends on managerial competence and media perception rather than ideological persuasion.

Governments that fail to deliver results quickly lose public trust, regardless of ideological positioning. Consider Singapore’s model, where authoritarian efficiency in healthcare and education sustains support without democratic ideals. Or the rapid fall of leaders during the 2020s energy crises, where voters punished incumbents for high prices, not policy philosophy.

The decline of long-term utopias is another hallmark. Classic ideologies were future-oriented, promising utopias—classless societies, national greatness, moral salvation. The post-ideological era, by contrast, is characterized by shortened time horizons. Climate anxiety, economic uncertainty, and technological disruption have made long-term visions less persuasive.

Political discourse is dominated by immediate risks and incremental fixes rather than transformative dreams. Hope has been replaced by risk management, as seen in global climate accords that focus on adaptation metrics rather than revolutionary overhauls. In the wake of AI advancements by 2026, policies emphasize ethical guidelines and job retraining over utopian visions of a post-work society.

Narrative politics and emotional mobilization have filled the void left by ideology. In place of doctrine, politics increasingly relies on narratives and emotions. Social media platforms reward simplicity, outrage, and personalization rather than ideological depth. Political communication is less about convincing citizens of a worldview and more about shaping perception, fear, and identity.

This narrative-driven politics thrives on symbolism, slogans, and spectacle—think of viral campaigns like “Make America Great Again” or “Build Back Better,” which evoke emotion without detailed programs. Truth becomes secondary to resonance, fostering a politics that is highly mobilizing but often shallow and unstable, prone to misinformation and echo chambers.

The commanding grip of grand ideologies has greatly weakened but it would be mistaken to proclaim them entirely extinct. They endure in diluted, hybridized, or largely symbolic versions and can re-emerge with surprising force during moments of acute crisis, armed conflict, societal upheaval, or rapid technological and cultural transformation

The blurring of left and right underscores this shift. Traditional ideological divisions—left versus right, state versus market—have lost clarity. Many contemporary movements combine elements that would once have been incompatible: economic protectionism with cultural conservatism, as in populist parties across Europe; welfare nationalism with market capitalism, evident in Nordic models; or environmentalism with corporate innovation, like green tech initiatives. This blurring reflects the erosion of ideological boundaries and the rise of situational politics driven by context rather than doctrine.

The technological rationality emerges as a new authority. In the absence of ideology, technology and data increasingly serve as sources of legitimacy. Algorithms, metrics, and expert systems are invoked to justify decisions in governance, economics, and social policy. From predictive policing to algorithmic welfare distribution, technocratic approaches appear neutral but often mask value choices. In a post-ideological age, technical expertise frequently carries more authority than philosophical argument, as seen in the reliance on data dashboards during pandemics or AI-driven economic forecasting.

Is the War of Ideas Truly Over?

While the dominance of ideology has diminished, it would be misleading to declare its complete disappearance. Ideologies persist in weakened, hybrid, or symbolic forms, resurfacing during crises, wars, or periods of rapid change. The Russia-Ukraine conflict since 2022, for instance, has revived nationalist and democratic ideologies in rhetoric, though pragmatic alliances dominate strategy. Moreover, the absence of strong ideologies does not necessarily lead to harmony; it may produce confusion, polarization, and manipulation by elites who exploit narrative voids.

Some critics argue that the post-ideological era is itself an illusion—that ideology has merely gone underground, disguised as common sense, nationalism, or technological inevitability. Thinkers like Slavoj Žižek contend that capitalism has become the unspoken ideology, presenting itself as natural rather than constructed. Others warn that the vacuum left by declining ideologies may be filled by authoritarianism, misinformation, or nihilism, as seen in the rise of conspiracy theories on platforms like X.

Living After Ideological Certainty

The transition from a war of ideas to a post-ideological era marks a fundamental shift in how societies understand power, belief, and legitimacy. Grand narratives no longer command unquestioned loyalty. Instead, politics operates through pragmatism, identity, emotion, and performance, fostering a more fluid but volatile world.

Policies once deemed ideologically taboo—such as welfare nationalism, green capitalism, or pragmatic alliances—are now seen as necessary responses to complex realities. At the same time, individuals enjoy greater freedom to shape personal ethical frameworks beyond doctrinal purity, creating space for more nuanced, tolerant, and inclusive civic discourse

Ultimately, the war of ideas—as it was waged across the bloody twentieth century through clashing grand narratives of communism, fascism, liberalism, and religious absolutism—has largely subsided. The grand ideological battles that once mobilized entire societies, inspired revolutions, and justified global conflicts have given way to a more fragmented, provisional landscape.

Yet this does not mark the end of contention or the triumph of some final harmony; rather, it inaugurates a new phase in human political existence. The struggle to define values, meaning, and collective purpose in an increasingly fragmented world has only just begun, and it unfolds under conditions far more fluid and uncertain than those of the ideological age.

In this post-ideological era, rigid doctrines no longer hold unquestioned sway. Pragmatism reigns where once dogma prevailed, identities assert themselves where universal theories once claimed transcendence, and performance—measured in immediate results, emotional resonance, and crisis management—often trumps philosophical coherence as the basis of legitimacy.

The blurring of left and right, the modular assembly of beliefs from disparate sources, the rise of narrative-driven mobilization through digital spectacle, and the elevation of technological rationality as a seemingly neutral arbiter all reflect this profound shift. Grand utopias have receded into the background, replaced by shortened time horizons focused on risk mitigation, incremental adaptation, and the management of pressing threats like climate disruption, economic volatility, and rapid technological change.

This transition carries profound opportunities. The decline of totalizing ideologies can liberate societies from the hubris and violence that so often accompanied ideological certainty, fostering greater flexibility, pluralism, and creative experimentation. Hybrid policies that once seemed heretical—welfare nationalism, green capitalism, pragmatic international alliances—become not only possible but necessary. Individuals gain space to craft personal ethics and worldviews without the pressure of doctrinal conformity, potentially enriching civic life with nuance and inclusivity.

The war of ideas may be over, but the harder task of forging values for a complex world has only begun. In the absence of grand ideologies, societies must negotiate meaning amid fragmented narratives, contested identities, and rapid technological change—demanding ethical imagination and dialogue rather than dogma. This quieter struggle unfolds through everyday choices in governance, culture, and coexistence, and its outcome will determine whether the post-ideological moment leads to renewal or drift

The risks are equally stark. Without shared ideological frameworks to anchor collective action, societies may struggle to muster the sustained will required for truly transformative responses to existential challenges. The vacuum invites cynicism, where short-term opportunism masquerades as pragmatism, elite manipulation thrives on narrative fragmentation, and emotional tribalism hardens into isolation. Identity, unmoored from broader visions of justice or progress, can devolve into zero-sum grievance politics.

Technocratic authority, cloaked in data and algorithms, may obscure underlying value choices and erode democratic accountability. In the worst scenarios, the absence of robust meaning-making structures could pave the way for resurgent authoritarianism, nihilistic withdrawal, or the unchecked spread of misinformation.

Navigating this fluid landscape demands not a retreat from engagement, but a deeper, more sophisticated form of it. Humanity must cultivate wisdom amid uncertainty—wisdom that recognizes complexity without descending into paralysis, that balances pragmatic problem-solving with ethical reflection, and that seeks new solidarities across fractured identities. This might mean revitalizing civic education to emphasize critical thinking and shared facts, building institutions that prize transparency and accountability over opaque expertise, and fostering hybrid discourses that weave personal experience with universal principles.

Ideas, in this era, should no longer dictate life through coercive certainty; instead, they must serve life—illuminating paths forward, nurturing responsibility, and sustaining hope in the face of fragmentation.

The post-ideological age is neither utopia nor dystopia; it is a condition of heightened contingency, where the choices we make about how to live together will determine whether flexibility becomes resilience or mere drift. The old war of ideas may be over, but the quieter, more intricate struggle to forge values worthy of a complex world has only entered its opening chapter. In meeting this challenge, humanity has the chance to prove that meaning can endure—and even flourish—beyond the shadow of ideological absolutes.

The post-ideological age is neither utopia nor dystopia; it is a condition of heightened contingency in which collective choices will determine whether flexibility matures into resilience or dissolves into drift. The end of the old war of ideas does not mean the end of belief, conflict, or power struggles—it marks the collapse of ideology’s monopoly over meaning. As grand doctrines recede, politics becomes more fluid, emotional, and outcome-driven, often effective in the short term yet fragile over time.

The real challenge before contemporary societies is not to resurrect exhausted ideologies, but to forge shared ethical frameworks capable of guiding action without claiming absolute truth. In a world governed increasingly by narratives, technology, and identity rather than coherent philosophies, the quieter and more demanding struggle is learning how to live responsibly and meaningfully—without the comfort of ideological certainties.

References

Bell, Daniel. The End of Ideology: On the Exhaustion of Political Ideas in the Fifties. 1960. New York: Free Press.

A foundational text on the decline of grand ideological systems.

Mannheim, Karl. Ideology and Utopia. 1936. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

A classic sociological analysis of ideology as socially conditioned knowledge.

Lyotard, Jean-François. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. 1979. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Introduces skepticism toward grand narratives, central to post-ideological thinking.

Hobsbawm, Eric. Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914–1991. 1994. London: Michael Joseph.

A definitive historical account of the ideological conflicts of the twentieth century.

Fukuyama, Francis. The End of History and the Last Man. 1992. New York: Free Press.

A key post–Cold War thesis on ideological exhaustion and liberal democracy.

Bauman, Zygmunt. Liquid Modernity. 2000. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Explores uncertainty, fragmentation, and fluidity in post-ideological societies.

Crouch, Colin. Post-Democracy. 2004. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Examines the hollowing out of ideological substance in contemporary democracies.

Castells, Manuel. Communication Power. 2009. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Analyzes how power operates through media, networks, and narratives.

Fisher, Mark. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? 2009. Winchester: Zero Books.

Explores how ideology survives by disguising itself as inevitability.

Han, Byung-Chul. Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power. 2017. London: Verso.

Examines power, consent, and self-regulation in a digital, post-ideological age.

Further Readings

Aron, Raymond. The Opium of the Intellectuals. 1957. London: Secker & Warburg.

A critique of ideological fanaticism and intellectual dogmatism.

Beck, Ulrich. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. 1992. London: Sage Publications.

Explores the shift from ideology-driven politics to risk management.

Brown, Wendy. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. 2015. New York: Zone Books.

Analyzes the erosion of democratic and ideological norms under neoliberalism.

Gray, John. Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia. 2007. London: Allen Lane.

Critiques modern political ideologies as secularized religious myths.

Habermas, Jürgen. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. 1989. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

A foundational work on the evolution of public discourse.

Harari, Yuval Noah. 21 Lessons for the 21st Century. 2018. London: Jonathan Cape.

Accessible reflections on ideology’s decline in a data-driven world.

Judt, Tony. Ill Fares the Land. 2010. New York: Penguin Press.

A moral reckoning with the collapse of social-democratic ideals.

Mishra, Pankaj. Age of Anger: A History of the Present. 2017. London: Allen Lane.

Links post-ideological resentment, identity politics, and global discontent.

Mouffe, Chantal. On the Political. 2005. London: Routledge.

Challenges post-ideological consensus and argues for productive political conflict.

Postman, Neil. Amusing Ourselves to Death. 1985. New York: Viking Penguin.

A media critique of spectacle replacing serious political discourse.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. 2019. New York: PublicAffairs.

Explores how technological power increasingly replaces ideological persuasion.

Žižek, Slavoj. The Sublime Object of Ideology. 1989. London: Verso.

Argues that ideology persists even when societies claim to be post-ideological.