By Subhash Dhuliya

Journalism today faces unprecedented challenges and opportunities. The digital revolution, the explosion of information, artificial intelligence, and evolving audience expectations are redefining how news is produced, distributed, and consumed. The once-stable world of journalism has become a dynamic and uncertain ecosystem shaped by constant technological disruption and new forms of audience engagement.

In this changing landscape, journalism education must be reimagined — not by discarding its traditional foundations but by blending them with digital fluency, critical thinking, multimedia storytelling, and ethical awareness. The goal is to prepare a new generation of journalists who can think, analyze, and adapt with both intellectual depth and practical agility.

The field of journalism is undergoing a profound transformation. The traditional definition of news — once guided by editorial judgment, professional hierarchies, and deadlines — has given way to an era of continuous updates, audience analytics, and algorithmic curation. Artificial intelligence now shapes not only how stories are discovered and distributed but also how they are written, personalized, and consumed. In such an environment, journalism education must evolve beyond vocational training to equip students with the intellectual, technical, and ethical tools needed to navigate a complex media world.

Where Traditional Core Concepts Stand

Traditional journalism education has long emphasized the values of accuracy, fairness, balance, attribution, and truthfulness. These remain the ethical backbone of credible reporting and continue to provide the moral compass of the profession. The 5Ws and How — Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How — still define journalistic inquiry, ensuring that news remains factual and comprehensive. Yet, their application has changed dramatically. Verification today extends beyond cross-checking quotes; it includes identifying deepfakes, analyzing metadata, and detecting algorithmic manipulation. Fairness demands not just multiple viewpoints but representation of voices historically excluded from mainstream discourse. The task, therefore, is not to replace the traditional values of journalism but to recontextualize them for a digital, data-driven, and participatory age.

The digital revolution has dismantled the old boundaries between print, broadcast, and online journalism. What was once a linear process of reporting and publishing is now a constant cycle of interaction and iteration. The media environment today is characterized by information overload, misinformation, and rapid shifts in audience behavior. Newsrooms increasingly rely on automation and analytics, while audiences encounter news through fragmented feeds and algorithmic recommendations. This convergence demands that journalism curricula go beyond teaching tools; they must nurture judgment, critical reasoning, and contextual understanding. Students must learn to decode complex media systems, interpret data responsibly, and understand how algorithms influence what people know and believe.

Balancing Theory and Practice

Balancing theory with practice remains central to journalism education. Simulated newsrooms, multimedia projects, and real-world assignments help students integrate professional rigor with creative experimentation. Universities must blend conceptual grounding with hands-on experiences, combining newsroom ethics with data visualization, social media strategy, and digital production. Partnerships between academia and industry are crucial. Collaboration with news organizations allows students to understand professional workflows, new editorial roles, and emerging trends such as audience engagement, AI-assisted reporting, and solutions journalism. A culture of lifelong learning must also be encouraged — with flexible, modular programs enabling working journalists to reskill and adapt as technology evolves.

Creativity, Critical Thinking and Media Literacy

In an age where artificial intelligence is automating routine tasks, creativity remains a key differentiator. Machines may process data, but human judgment, imagination, and emotional intelligence cannot be replaced. Journalism education must prioritize fostering creativity, encouraging students to develop original storytelling approaches, explore innovative formats, and connect with audiences meaningfully.

Critical thinking and media literacy are no longer optional; they are the foundation of modern journalism. In an era of disinformation and deepfakes, the ability to question sources, verify facts, and contextualize narratives has become essential. Journalists must understand how algorithms curate attention, how AI systems shape visibility, and how data can be both a source of truth and a tool of manipulation. Media literacy must therefore be a core component of journalism education, empowering students not only to report on technology but also to critique it. As Charlie Beckett (2023) of the LSE’s JournalismAI project argues, the future of journalism depends on how well journalists understand and ethically manage AI technologies that now shape the public sphere.

Cross-Disciplinary Approach

Modern journalism also requires a cross-disciplinary approach. Reporting on climate change demands some grasp of environmental science; covering financial policy requires fluency in data and economics; and investigating AI itself calls for an understanding of computer ethics and governance. Journalism schools must open their curricula to the social sciences and humanities, . This not only enriches journalistic understanding but also ensures that students see news as an interconnected web of issues rather than isolated events. The best journalism, after all, explains how the world works — and that requires deep intellectual engagement across fields.

Rethinking the Relationship Between Journalists and Audiences.

Audiences today are no longer passive recipients of news; they are collaborators, critics, and co-creators. Journalism education should therefore emphasize engagement, transparency, and dialogue. Students should learn to interpret audience data not as click metrics but as insights into trust and participation. Courses in community journalism, participatory storytelling, and constructive dialogue can help future journalists rebuild trust in an era of polarization and skepticism.

The expansion of digital and entertainment media also means journalism education must extend beyond traditional news. Storytelling now happens across platforms — from podcasts and documentaries to data interactives. Programmes must prepare students to create content for diverse formats, combining editorial sense with visual literacy and production skills. Creativity has become a vital professional competency. As automation handles repetitive tasks, the journalist’s distinct value lies in imagination, empathy, and human interpretation — qualities AI cannot replicate.

Integrating Technology, AI, and Storytelling

Artificial intelligence is now transforming every stage of journalism — from content discovery and transcription to personalization and predictive analytics. In the classroom, this requires a shift in perspective: AI must be taught not as a threat but as a tool that can enhance journalistic capabilities when used responsibly. Students should be trained in both the opportunities and ethical risks of AI — including bias in algorithms, transparency in automated content, and accountability in AI-assisted decision-making. Learning to use AI-driven tools for verification, pattern recognition, and data analysis should be matched with instruction on editorial judgment, ensuring machines complement rather than replace human creativity and empathy.

Digital technologies—from data visualization and mobile reporting to artificial intelligence—are now central to journalism. AI is transforming how stories are researched, verified, and distributed, automating routine tasks but also demanding new ethical frameworks. Students should be trained not only in traditional storytelling but also in the use of generative tools, data analysis, coding basics, and verification technologies. Journalism education must encourage a critical understanding of AI’s possibilities and pitfalls: how algorithms amplify bias, how automation affects credibility, and how human editorial judgment remains essential amid machine-assisted news production.

Information Overload and the Rise of Evidence-Based Journalism

The problem of information overload underscores nearly every challenge facing journalism today. Audiences are bombarded with more data than ever before — from social feeds and live streams to algorithmic news alerts. This abundance, while empowering, can create confusion, fatigue, and mistrust. Journalists must therefore learn to filter, interpret, and contextualize information to help audiences make sense of complexity. Evidence-based and data-driven journalism provides a way forward, enabling reporters to analyze vast datasets and extract meaningful insights that bring clarity rather than clutter. As Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel (2010) argue in Blur: How to Know What’s True in the Age of Information Overload, journalism’s task today is not to add to the noise but to make meaning from it.

To navigate this complexity, journalism education must focus on developing cognitive resilience — the ability to synthesize information, evaluate competing narratives, and resist manipulation. Students should be trained in the use of verification tools, open-source intelligence, and data visualization techniques that enhance both transparency and public understanding. Journalism education must therefore teach students to filter data, prioritize relevance, and practice evidence-based reporting grounded in facts, data, and context. This approach promotes critical thinking and analytical depth, enabling journalists to identify patterns, verify authenticity, and present complex issues with clarity. This approach fosters journalism that informs rather than overwhelms, grounding facts in evidence and reason.

Linking Academia and Industry- Facilitating Lifelong Learning

Strong connections between media education and industry practice are essential. Partnerships with media organizations expose students to professional workflows, emerging roles, and technological standards. Modern journalists are expected to be multi-skilled, capable of writing, shooting, editing, and distributing content across platforms. Curricula should reflect this convergence, preparing students for diverse roles in newsrooms, production houses, digital media, and emerging AI-driven content operations.

Given the rapid pace of technological change, journalism education cannot end at graduation. Universities and media institutions should offer modular, short-term courses for mid-career professionals to reskill. Building a culture of lifelong learning ensures practitioners remain relevant in an industry where tools, platforms, and audience expectations evolve constantly.

For decades, journalism curricula mirrored the industrial model of news production: reporting, editing, layout, and broadcast routines. Today, however, news is produced in a fluid, networked environment where journalists must think digitally first. Journalism schools need to move beyond training for jobs in legacy media and instead cultivate adaptability, digital fluency, and entrepreneurial skills that empower students to navigate multiple platforms. This requires active engagement with the industry to stay informed about the latest developments in an era of rapid transformation.

Innovation in Teaching Methodologies

Faculty must innovate to meet the challenges of the information age. Teaching should integrate digital tools, data analysis, and multimedia production while encouraging critical inquiry and intellectual rigor. Students should learn to investigate complex stories, follow the money, analyze trends, and uncover underreported angles. This requires research skills, lateral thinking, and an investigative mindset, ensuring graduates are capable of producing insightful and impactful content.

Expanding Beyond Journalism

Media education must evolve beyond the narrow confines of traditional journalism to address the dynamic demands of a rapidly transforming industry. The proliferation of over-the-top (OTT) platforms, social media, and digital content ecosystems, alongside the expansion of news and entertainment sectors, has reshaped how media is produced, consumed, and monetized. To prepare students for this multifaceted landscape, educational programmes must incorporate disciplines such as entertainment arts, content creation, digital storytelling, and multimedia production. These areas not only reflect the industry’s current needs but also empower students to navigate and innovate within an increasingly digital and interconnected world.

The rise of OTT platforms like Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Disney+ has revolutionized content consumption, prioritizing on-demand, high-quality storytelling over traditional broadcast models. Similarly, platforms like YouTube, and Instagram have democratized content creation, enabling individuals to reach global audiences. Media education must train students to create content tailored to these platforms, understanding their unique formats, algorithms, and audience expectations.

Digital storytelling goes beyond traditional linear narratives, incorporating interactive elements, transmedia approaches, and user-generated content integration. For instance, a story might begin on a podcast, continue through social media posts, and conclude in a web series, creating a cohesive yet multifaceted experience.

Journalism education must move beyond the outdated model of training students solely to become traditional journalists. These skills are now applicable across a wide range of industries, reflecting the evolving role of media professionals.

To align with industry trends and prepare students for sustainable careers, media education programmes should adopt a multidisciplinary curriculum, integrating courses in digital media, data analysis, creative writing, and emerging technologies alongside traditional journalism training.

The media landscape is no longer confined to traditional journalism, and education must reflect this shift. By embracing disciplines like entertainment arts, digital storytelling, and content creation, programmes can prepare students to excel in a variety of roles across news, entertainment, and corporate sectors. Simultaneously, journalism education should redefine its purpose, recognizing the versatility of journalistic skills while addressing the profession’s challenges. Moreover, journalism as a profession often lacks appeal due to its poor work-life balance and relatively low pay compared to other professional careers, except for a small elite at the top.

Entrepreneurship and innovation

Entrepreneurship and innovation are now indispensable elements of journalism training. As traditional business models collapse, independent media ventures, nonprofit newsrooms, and digital start-ups have become vital spaces for innovation. Students must learn to think entrepreneurially — to design new products, experiment with audience engagement, and build sustainable funding models. Journalism education should nurture creators, not just employees, empowering graduates to drive the evolution of the industry.

Ethical Awareness and Societal Context

Ethics remains the moral anchor of journalism. But the nature of ethical dilemmas has changed. In a borderless digital environment, issues such as privacy, consent, hate speech, and AI bias are increasingly complex. Journalism programmes must help students grapple with these tensions, ensuring they understand both traditional professional standards and the emerging ethics of algorithmic and data-driven storytelling. Responsible journalism in the digital era means being aware not only of what one reports but also of how technology mediates that reporting.

As media professionals navigate an era of information giants and algorithmic influence, they must understand the ethical implications of their work. The concentration of digital power raises questions about privacy, democracy, and the manipulation of public opinion. Students must be trained to critically examine these dynamics and understand their broader societal impact. Ethical grounding, media literacy, and critical thinking equip future journalists to act responsibly in an environment where misinformation, persuasion, and data-driven influence are pervasive.

The ethical challenges of journalism are magnified in a borderless, digital environment. Issues such as privacy, consent, hate speech, and cultural sensitivity must be revisited in light of social media virality and global reach. Journalism programs should update their ethics training to account for these complexities, helping students navigate dilemmas that arise when a local story instantly becomes global.

Preparing for the Future

Restructuring journalism education does not mean discarding the fundamentals. Accuracy, fairness, verification, and accountability remain at the heart of training. The goal is a new balance: preserving these timeless values while equipping students with digital fluency, AI literacy, critical thinking, cross-disciplinary knowledge, creativity, and entrepreneurial skills. Journalism schools must prepare graduates to lead in a complex, convergent, and technology-driven media environment.

Restructured journalism education is not merely about teaching new tools or technologies—it is about creating adaptive, thoughtful, and creative media professionals capable of upholding journalistic values and ethics while shaping the future of information, storytelling, and AI-augmented media. By preparing students to navigate information overload, engage ethically with audiences, and leverage AI responsibly, journalism education can ensure that the next generation of media professionals thrives in a rapidly evolving world.

Theoretical Foundation

A restructured journalism education must rest on a strong theoretical foundation. Technical proficiency alone cannot sustain meaningful journalism. A grounding in the social sciences and humanities is indispensable, as it provides the intellectual scaffolding for interpreting events and understanding their broader significance. Theory equips journalists to ask deeper questions, identify underlying structures of power, and engage critically with the world. As Barbie Zelizer (2017) notes in What Journalism Could Be, theory offers the moral and philosophical grounding that keeps journalism connected to its democratic purpose. Without it, journalism risks becoming reactive, shallow, and detached from its social mission.

In the end, restructuring journalism education is not about replacing the old with the new but about integrating enduring values with contemporary demands. Accuracy, fairness, and accountability must coexist with AI literacy, creativity, and global awareness. Journalism schools should cultivate graduates who are not just skilled communicators but informed thinkers — capable of interpreting complexity, resisting manipulation, and shaping narratives that strengthen public life. As Mustafa Suleyman (2023) reminds us in The Coming Wave, humanity’s greatest challenge is learning to coexist with intelligent technology. Journalism, as the interpreter of our times, must lead that conversation.

Epilogue: The Intellectual Foundation of Modern Journalism

A robust theoretical foundation is essential for journalists, serving as the intellectual backbone of their craft. Grounded in the social sciences and humanities, it provides insight into the social, political, economic, and cultural forces that shape events and human behavior. Without this grounding, reporting risks being superficial or fragmented. Theory enables journalists to ask incisive questions, evaluate sources critically, interpret complex developments, and uncover deeper implications, giving meaning and context to their work.

While technical skills like writing, filming, or editing are vital, they cannot replace the intellectual rigor needed to navigate intricate realities. Understanding history, politics, culture, and philosophy allows journalists to contextualize events, challenge assumptions, and craft narratives that illuminate human experience. In short, theory is not supplementary—it is the foundation that gives journalism purpose, coherence, and credibility.

Integrating practical skills with this intellectual grounding equips journalists to uphold ethical standards, provide informed analysis, and address the challenges of modern media. In the digital age, critical thinking, ethical reasoning, and informed judgment—qualities nurtured by theory—remain indispensable. Without them, reporting risks becoming shallow, decontextualized, or misleading. A journalist’s ability to interpret society, contribute meaningfully to public discourse, and maintain trust depends on this core foundation, ensuring journalism remains a vital, transformative force.

Without understanding society, a journalist is like a sailor without a compass—technically skilled but directionless.

References

- Eide, M., Sjøvaag, H., & Larsen, L. O. (2023). Journalism Re-examined: Digital Challenges and Professional Orientations. Routledge.

- Kovach, B., & Rosenstiel, T. (2010). Blur: How to Know What’s True in the Age of Information Overload. Bloomsbury Press.

- Suleyman, M. (2023). The Coming Wave: Technology, Power, and the Twenty-First Century’s Greatest Dilemma. Crown.

- Beckett, C. (2023). JournalismAI Report: Artificial Intelligence and the News Industry. LSE Polis.

- Zelizer, B. (2017). What Journalism Could Be. Polity Press.

- Bell, E. (2020). Journalism in an Age of Information Disorder. Tow Center for Digital Journalism.

About the Author:

Prof. Subhash Dhuliya is a media educator, researcher, and commentator who has spent his career exploring the intersections of journalism, communication, and public knowledge. He is the Founder-Director of Newswriters.in, an independent platform devoted to strengthening journalism education and promoting media literacy and critical thinking.

He has served as Vice Chancellor of Uttarakhand Open University and as Professor at IGNOU, IIMC, and CURAJ, contributing extensively to media scholarship and professional training in India. Earlier in his career, he worked as Assistant Editor at The Sunday Times and Navbharat Times, and as Chief Sub-Editor at Amrita Prabhat. He also edited the research journals Communicator and Sanchar Madhyam of the Indian Institute of Mass Communication (IIMC).

Acknowledgement: The conceptual framework and ideas presented in this article are solely those of the author with drafting assistance provided by ChatGPT (OpenAI)

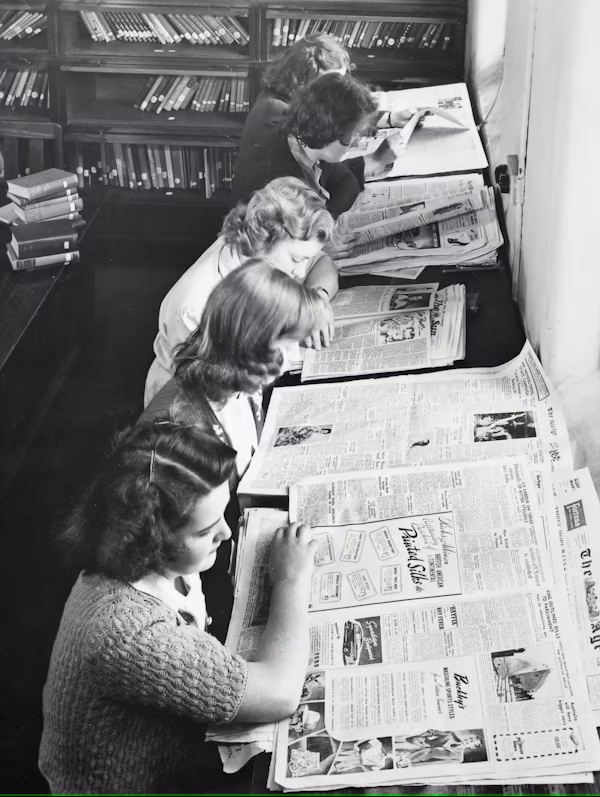

Photo: Museums Victoria. Unsplash