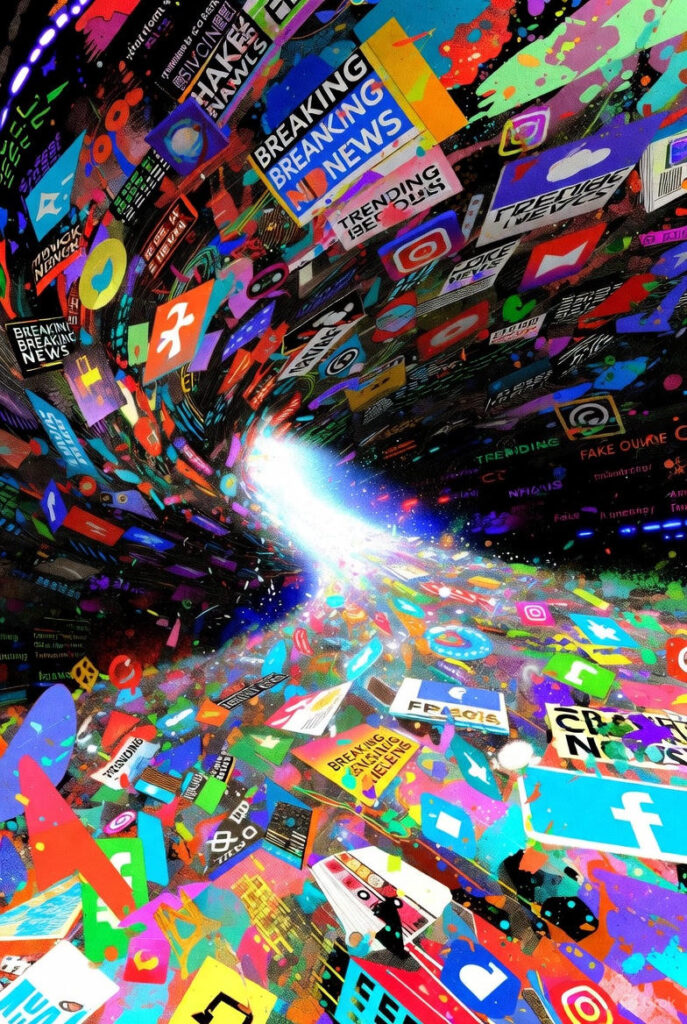

We are living through an Infodemic Revolution—a relentless flood of information that has turned news into noise, burying verifiable truth under layers of speed, sensationalism, algorithmic curation, and AI-amplified narratives. In 2025, with global trust in media stagnating at around 40% (Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2025) and two-thirds of people struggling to distinguish credible information from misinformation (Edelman Trust Barometer 2025), the pursuit of virality continues to eclipse accuracy.

In this age of boundless information abundance, true knowledge has become increasingly scarce, and wisdom—once the quiet fruit of reflection and experience—now feels almost entirely absent from the endless stream.

This article examines the mechanisms driving this erosion—from echo chambers and deepfakes to grievance-fueled disinformation—and proposes actionable pathways for journalists, citizens, platforms, and policymakers to restore clarity, rebuild shared reality, and reclaim truth in an increasingly polarized, post-truth world.

By Subhash Dhuliya

From Scarcity to Overload: The Evolution and Nature of Information Access

In the pre-digital era, information was a scarce commodity. News arrived through limited channels—newspapers delivered once a day, radio broadcasts at scheduled times, or television news in the evening. Access to facts required effort, and the gatekeepers—editors and journalists—ensured a degree of curation and verification.

Today, however, editors have largely transformed from traditional gatekeepers into gatewatchers: rather than deciding what gets published, they increasingly monitor, react to, and amplify stories that have already gained traction online, often prioritizing virality and audience metrics over independent curation and rigorous verification. This shift has weakened the traditional filtering role, allowing unvetted or sensational content to flow more freely into the public sphere before any editorial judgment is applied.

The digital revolution shattered this paradigm. The advent of the internet in the 1990s, followed by the proliferation of smartphones in the 2000s, ushered in an era of abundance. Suddenly, information was everywhere, accessible at any time.

Blogs, online news portals, and early social media platforms democratized content creation, allowing anyone to publish and share ideas. This shift promised empowerment: knowledge at our fingertips, global connectivity, and the breakdown of information monopolies.

However, this same democratization also turned social media into a primary platform for unverified information and fake news, where anyone could spread rumors, manipulated content, or deliberately false narratives without traditional editorial oversight or verification.

As a result, the rapid, unchecked sharing of such material often amplified misinformation far faster than accurate reporting, contributing to confusion, polarization, and the erosion of trust in digital information ecosystems.

However, abundance quickly morphed into overload. By the 2010s, the 24/7 news cycle became the norm, fueled by platforms like Twitter (now X), Instagram, and TikTok. Smartphones turned into constant companions, bombarding users with push notifications, live updates, and viral threads.

The explosion of user-generated content meant that professional journalism competed with amateur posts, memes, and influencer endorsements. Today, the average person encounters thousands of pieces of information daily, from email alerts to social media scrolls, leading to a state where quantity eclipses quality.

In the attention economy, truth is often the first casualty. When clicks and shares dictate visibility, accuracy becomes secondary to allure.

This transition has profound implications. In an attention economy, where human focus is the ultimate currency, news is no longer just information—it’s a product designed to captivate. Platforms monetize engagement through ads, turning users into commodities whose time and data are sold to the highest bidder.

As a result, content creators prioritize speed over accuracy and virality over verification. Algorithms, powered by artificial intelligence, amplify what keeps users hooked: sensational headlines, emotional triggers, and polarizing narratives. The Infodemic Revolution is thus not merely about more information; it’s about how this deluge reshapes our perception of truth.

Information Overload: When Volume Erodes Understanding

Information overload occurs when the sheer volume of data exceeds an individual’s capacity to process it effectively. Coined by futurist Alvin Toffler in 1970, the term has never been more relevant. Cognitive science tells us that human attention spans are finite—research from Microsoft in 2015 suggested they’ve shrunk to about eight seconds, shorter than that of a goldfish. In this context, the constant influx of news fragments—headlines, snippets, and alerts—overwhelms our mental bandwidth.

News fragmentation exacerbates this issue. Traditional articles provided context and depth, but modern consumption favors bite-sized updates: 280-character tweets, 15-second videos, and infinite scrolls.

These formats deliver information without meaning, leaving audiences with superficial knowledge. Emotional fatigue sets in as users navigate conflicting reports, leading to withdrawal and apathy. Paradoxically, people feel informed because they’re constantly exposed to “news,” yet they remain uninformed or misinformed, unable to synthesize or critically evaluate the flood.

Core insight: Overload doesn’t just confuse; it desensitizes. In a world of endless noise, important signals get lost, fostering a cycle of disengagement. This erosion of understanding paves the way for misinformation to flourish, as exhausted minds default to heuristics like confirmation bias rather than rigorous scrutiny.

Overload isn’t just about too much data—it’s about losing the ability to discern what’s real amid the relentless barrage.

Truth Lost in Noise: Mechanisms and Consequences

Truth becomes buried in noise through several insidious mechanisms. First, fake news and disinformation ecosystems thrive in digital spaces. These include bot networks, troll farms, and coordinated campaigns that amplify falsehoods.

Second, echo chambers and filter bubbles—curated by algorithms—reinforce existing beliefs, isolating users from diverse perspectives.

Third, data manipulation and selective framing twist facts to fit narratives, often through cherry-picking or out-of-context quotes. Fourth, deepfakes and synthetic media, enabled by AI, create hyper-realistic forgeries that deceive even experts. Finally, paid influencers, propaganda, and astroturfing simulate grassroots support for agendas, blurring authenticity.

In the noise, truth isn’t hidden—it’s drowned out by deliberate deceptions and algorithmic amplifications.

The consequences are dire. Public trust in media has plummeted; a 2023 Edelman Trust Barometer reported that only 59% of global respondents trust news sources. Institutions, science, and democracy suffer as misinformation erodes shared facts. Polarization intensifies, with information weaponized to divide societies.

In a post-truth society, objective reality fragments, replaced by subjective “truths” shaped by ideology. This collapse threatens everything from public health to electoral integrity.

Case Studies: Real-World Impacts of the Infodemic

To illustrate, consider the COVID-19 infodemic. In 2020-2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared an “infodemic” as unverified claims about cures, vaccines, and origins flooded platforms. Vaccine rumors, such as microchip conspiracies, deterred uptake and prolonged the pandemic. In India, messages on WhatsApp claimed salt water or herbal remedies could prevent infection, shared with good intentions but lacking evidence, leading to public confusion (Al Jazeera, MDPI).

Another example is election misinformation. During India’s 2019 national elections, 13% of images in politically oriented WhatsApp groups were known misinformation, often designed to sway votes or incite tension.

Case studies reveal the infodemic’s human cost—from health crises to violence—underscoring the urgency of intervention.

Communal misinformation via messaging apps has tragic outcomes. In 2018, WhatsApp rumors about “child-lifters” led to the Karbi Anglong lynching in Assam, killing two innocents (Wikipedia). Similarly, the 2020 Palghar mob lynching in Maharashtra stemmed from lockdown-era whispers about thieves, resulting in vigilante violence (Wikipedia). These cases highlight how overload amplifies harm, turning noise into real-world chaos.

Reclaiming Truth: Pathways and Solutions

Reversing the Infodemic Revolution requires multifaceted strategies. For media professionals, embracing “slow journalism” is key: prioritizing in-depth reporting, verification protocols, and transparency in sourcing. Fact-checking initiatives like FactCheck.org or India’s Alt News demonstrate how rigorous scrutiny can counter noise.

Citizens and students must cultivate media literacy. Building a personal news diet involves curating trusted sources, practicing lateral reading (cross-verifying claims), and using tools like Google Fact Check Explorer. Source literacy—evaluating credibility based on authorship, evidence, and bias—is essential to navigate overload.

Case studies reveal the infodemic’s human cost—from health crises to violence—underscoring the urgency of intervention.

Platforms and policymakers bear significant responsibility. Demanding algorithmic transparency can mitigate filter bubbles, while content regulation—such as EU’s Digital Services Act—holds tech giants accountable. Incentives for quality content, like rewarding verified posts, could shift the attention economy toward truth.

In India, addressing WhatsApp’s role is crucial. Studies show viral forwards often repeat debunked propaganda , so features like forward limits and fact-check integrations are steps forward. Ultimately, reclaiming truth demands collective action: education, innovation, and ethical design to prioritize clarity over chaos.

Defining Key Terms: Clarifying the Lexicon of Deception

To navigate this landscape, understanding terminology is vital.

- Infodemic: An overwhelming amount of information—accurate, partially true, or false—that spreads rapidly, making trustworthy sources hard to find. Example: COVID-19’s flood of claims created panic and confusion (WHO).

- Information Overload: Volume exceeding processing capacity, leading to stress and poor decisions. Example: Endless breaking-news alerts during disasters overwhelm audiences.

- Misinformation: False information spread without harmful intent. Example: Sharing unverified COVID remedies believing they’re true.

- Disinformation: Deliberately false information to mislead. Example: Deepfake political videos to influence elections.

- Malinformation: True information shared maliciously. Example: Leaking private emails to damage reputations.

Summary Table:

| Term | What it Means | Intent | Example |

| Infodemic | Too much info causing confusion | — | COVID-19 flood of claims |

| Information Overload | More info than we can process | — | Endless breaking-news alerts |

| Misinformation | False info, believed to be true | Not harmful | Home remedies curing COVID |

| Disinformation | False info created to deceive | Harmful/strategic | Deepfake political video |

| Malinformation | True info used to harm | Harmful | Leaked personal emails/photos |

Indian Context: Localized Lessons from the Infodemic

In India, the infodemic manifests uniquely due to high mobile penetration and reliance on apps like WhatsApp. During COVID-19, unverified remedies circulated widely, contributing to health misinformation . Political disinformation, as in 2019 elections, exploited groups to spread manipulated images.

Why the News We Receive Is No Longer Information

The digital age promised democratized knowledge but delivered chaos. News, once a public service, is now commodified in the attention economy, rewarding outrage over insight. Algorithms curate echo chambers, while AI-generated content blurs reality. The paradox: more information, less truth.

To combat this, we must rethink journalism, literacy, and systems. Questions remain: How to reclaim truth? Rebuild trust? Design for clarity? The Infodemic Revolution is ongoing, but with awareness and action, we can navigate toward a more informed future.

The Infodemic Revolution is not an inevitable endpoint but a warning: the more information we produce, the greater the risk that truth becomes indistinguishable from noise. As grievance, polarization, and the legitimization of disinformation as tools for change deepen institutional distrust (Edelman Trust Barometer 2025), the path forward lies in deliberate, collective action—embracing slow, transparent journalism; fostering widespread media and source literacy; demanding algorithmic accountability; and designing systems that reward evidence over engagement.

By prioritizing clarity over chaos, rebuilding trust through verifiable facts, and equipping individuals to navigate the deluge, we can transform the current information crisis into an opportunity to forge a more resilient, informed society—one where truth is not drowned out, but amplified for the common good. The choice is ours: surrender to the noise, or reclaim the signal.

The Infodemic Revolution is not inevitable. It is a warning.

- The more information we produce, the harder truth becomes to find.

- Grievance, polarization, and disinformation now fuel distrust in institutions

- The path forward requires deliberate action.

- Embrace slow, transparent journalism.

- Build widespread media and source literacy.

- Demand algorithmic accountability from platforms.

- Design systems that reward evidence over engagement.

- Prioritize clarity over chaos.

- Rebuild trust through verifiable facts.

- Equip people to navigate the flood of information.

- We can turn this crisis into opportunity.

- We can create a more resilient, informed society.

- Truth can be amplified instead of drowned.

- The choice is clear: surrender to the noise or reclaim the signal.

References

Chiluwa, I. E. (Ed.). (2019). Deception, fake news, and misinformation online. IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-8913-6

Cosentino, G. (2020). Social media and the post-truth world order: The global dynamics of disinformation. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43613-1

Farkas, J., & Schou, J. (2019). Post-truth, fake news and democracy: Mapping the politics of falsehood. Routledge.

Islam, M. S., et al. (Eds.). (2021). The infodemic: Disinformation, geopolitics and the Covid-19 pandemic. I.B. Tauris/Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9780755640775

Kanefield, T., & Dorian, P. (2023). A firehose of falsehood: The story of disinformation. Candlewick Press.

McIntyre, L. (2018). Post-truth. MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series.

McIntyre, L. (2023). On disinformation: How to fight for truth and protect democracy. MIT Press.

McQuade, B. (2024). Attack from within: How disinformation is sabotaging America. Rowman & Littlefield.

Pomerantsev, P. (2019). This is not propaganda: Adventures in the war against reality. PublicAffairs.

Rid, T. (2020). Active measures: The secret history of disinformation and political warfare. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Simon, J., & Mahoney, R. (2022). The infodemic: How censorship and lies made the world sicker and less free. Columbia Global Reports.

van der Linden, S. (2023). Foolproof: Why misinformation infects our minds and how to build immunity. W. W. Norton & Company.

Articles

Brennen, J. S., Simon, F. M., Howard, P. N., & Nielsen, R. K. (2020). Types, sources, and claims of COVID-19 misinformation. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/types-sources-and-claims-covid-19-misinformation

Cinelli, M., Quattrociocchi, W., Galeazzi, A., Valensise, C. M., Brugnoli, E., Schmidt, A. L., Zola, P., Zollo, F., & Scala, A. (2020). The COVID-19 social media infodemic. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 16598. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73510-5

Garimella, K., & Eckles, D. (2020). Images and misinformation in political groups: Evidence from WhatsApp in India. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-030

Gaysynsky, A., Senft Everson, N., Heley, K., & Chou, W. Y. S. (2024). Perceptions of health misinformation on social media: Cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Infodemiology, 4, e51127. https://doi.org/10.2196/51127

Islam, M. S., Sarkar, T., Khan, S. H., Mostofa Kamal, A., Hasan, S. M. M., Kabir, A., … & Seale, H. (2020). COVID-19-related infodemic and its impact on public health: A global social media analysis. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 103(4), 1621–1629. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0812

Seelam, A., Choudhury, A. P., Liu, C., Goay, M., Bali, K., & Vashistha, A. (2024). “Fact-checks are for the top 0.1%”: Examining reach, awareness, and relevance of fact-checking in rural India. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.08172. https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.08172

Sharma, A. E., Khosla, K., Potharaju, K., Mukherjea, A., & Sarkar, U. (2023). COVID-19–associated misinformation across the South Asian diaspora: Qualitative study of WhatsApp messages. JMIR Infodemiology, 3, e38607. https://doi.org/10.2196/38607

World Health Organization. (2020). Managing the COVID-19 infodemic: Promoting healthy behaviours and mitigating the harm from misinformation and disinformation. WHO News Item. https://www.who.int/news/item/23-09-2020-managing-the-covid-19-infodemic-promoting-healthy-behaviours-and-mitigating-the-harm-from-misinformation-and-disinformation

Web Resources

Edelman. (2025). 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer: Bet on the future. https://www.edelman.com/trust/2025/trust-barometer (Global trust survey highlighting institutional trust erosion, polarization, and misinformation impacts; 25th annual edition, based on surveys from October–November 2024.)

World Health Organization. (2020). Call for action: Managing the infodemic. https://www.who.int/news/item/11-12-2020-call-for-action-managing-the-infodemic (Foundational WHO document on infodemic management during COVID-19.)

Al Jazeera. (2020, March 10). Misinformation, fake news spark India coronavirus fears. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/3/10/misinformation-fake-news-spark-india-coronavirus-fears (Reporting on early COVID-19 rumors and WhatsApp forwards in India.)

Wikipedia contributors. (2025). 2018 Karbi Anglong lynching. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2018_Karbi_Anglong_lynching (Incident details involving WhatsApp rumors leading to violence.)

Wikipedia contributors. (2025). 2020 Palghar mob lynching. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2020_Palghar_mob_lynching (Case study of lockdown-era misinformation triggering mob violence.)

Further Readings

- Harsin, J. (Ed.). (2023). Re-thinking mediations of post-truth politics and trust: Globality, culture, affect. Routledge. (Focuses on cultural infrastructures enabling post-truth.)

- Levitin, D. J. (2017). Weaponized lies: How to think critically in the post-truth era. Dutton. (Practical guide to critical thinking amid misinformation.)

- McIntyre, L. (2021). How to talk to a science denier: Conversations with flat Earthers, climate deniers, and others who doubt reason. MIT Press. (Strategies for countering denialism relevant to infodemics.)

- Rogers, R. (Ed.). (2020). The propagation of misinformation in social media: A cross-platform analysis. Amsterdam University Press.

- Simon, J. (2022). The infodemic: Censorship, lies, and the global pandemic response. Columbia Global Reports. (Examines government roles in amplifying misinformation.)

About the Author

Prof. Subhash Dhuliya is a distinguished academician, researcher, and educational administrator. He served as Vice Chancellor of Uttarakhand Open University and Professor at IGNOU, IIMC, and CURAJ. Earlier, he worked as Assistant Editor and Editorial Writer with the Times Group- Sunday Times and Navbharat Times, and as Chief Sub-Editor at Amrit Prabhat (Amrita Baza Patrika Group) . He has edited IIMC’s research journals Communicator and Sanchar Madhyam, founded Newswriters.in, and served as a UNESCO consultant for journalism education in the Maldives.