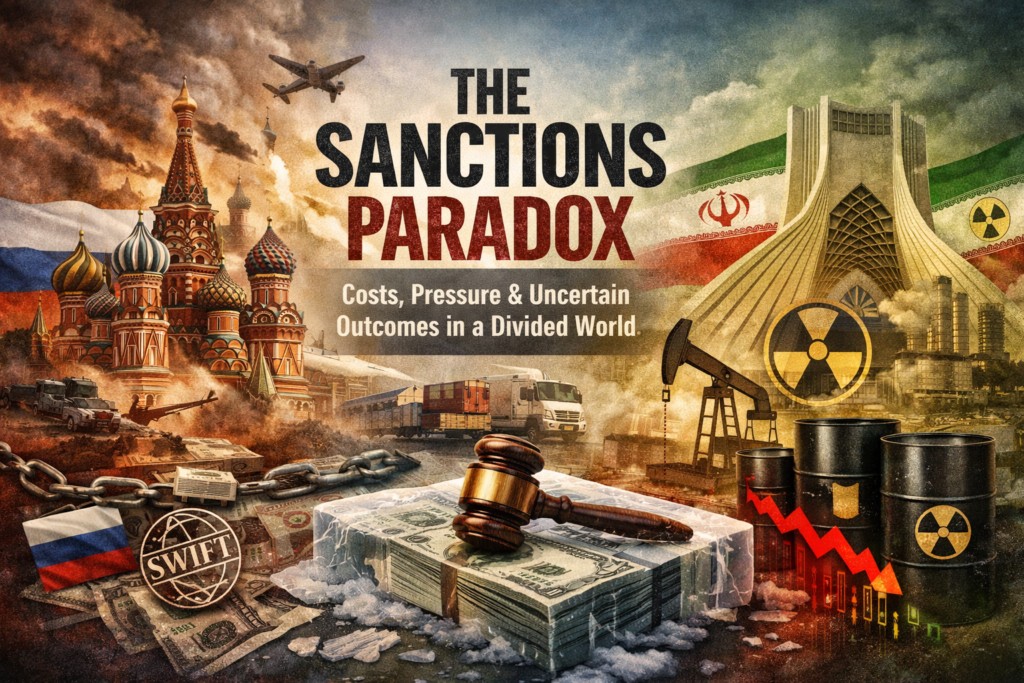

Sanctions have become the weapon of choice in modern geopolitics—high on symbolism, heavy on disruption, but uncertain in results. From Russia’s war economy surviving unprecedented Western pressure to Iran absorbing fresh rounds of punitive measures, recent cases expose a familiar paradox: sanctions impose costs and signal resolve, yet rarely compel strategic surrender. In an increasingly fragmented, de-dollarizing world, they reveal both the enduring power—and the hard limits—of economic coercion.

Successes and Failures of Sanctions: Lessons from History and the Present

By Newswriters News Desk

Economic sanctions, often described as tools of coercion short of war, represent a cornerstone of international relations. They involve the deliberate withdrawal of economic relations—such as trade embargoes, financial restrictions, or asset freezes—to influence the behavior of targeted states, entities, or individuals. While sanctions aim to enforce norms, deter aggression, or promote policy changes, their history reveals a complex interplay of power, ethics, and efficacy.

From ancient trade bans to modern “smart” sanctions, this analysis traces their evolution, examining how they have shaped global conflicts and diplomacy. Drawing on historical episodes, we explore their origins, transformations, and persistent challenges, highlighting both successes and humanitarian costs.

Ancient Roots and Pre-Modern Applications

The concept of sanctions predates modern nation-states, emerging as a form of economic warfare in antiquity. The earliest recorded instance dates to 432 BCE, when Athenian statesman Pericles issued the Megarian Decree, prohibiting merchants from the city-state of Megara from accessing Athenian markets and harbors. This measure, ostensibly a response to territorial disputes, strangled Megara’s economy and contributed to the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War. Here, sanctions were not merely punitive but strategic, leveraging economic interdependence to weaken rivals without immediate military engagement. This episode underscores an enduring theme: sanctions exploit vulnerabilities in trade networks, often escalating tensions rather than resolving them.

Throughout the medieval and early modern periods, sanctions evolved in form but retained their coercive essence. Religious institutions, such as the Catholic Church, employed excommunication and trade interdictions to enforce doctrinal compliance, effectively isolating non-compliant regions economically.

In the Age of Empires, European powers used naval blockades and embargoes during conflicts. A pivotal example is Napoleon’s Continental System (1806–1814), which banned British goods from Europe to undermine the United Kingdom’s economic dominance. Intended to starve Britain of markets, it instead provoked smuggling, alliances against France, and economic hardship across the continent. This failure highlighted a recurring analytical pitfall: sanctions often harm the sanctioning states or neutrals as much as the targets, due to interconnected economies.

By the 19th century, sanctions became more formalized amid rising globalization. The United States’ Embargo Act of 1807, under President Thomas Jefferson, prohibited American ships from trading with Britain and France amid the Napoleonic Wars, aiming to protect neutral rights and avoid war. However, it devastated U.S. exporters, leading to its repeal and illustrating how domestic political pressures can undermine sanction regimes. During the American Civil War, both the Union and Confederacy imposed blockades, further embedding sanctions in wartime strategy. These pre-modern uses reveal sanctions as blunt instruments, often indistinguishable from acts of war, with limited success in achieving long-term policy shifts.

The 20th Century: Institutionalization and the World Wars

The horrors of World War I catalyzed a paradigm shift, transforming sanctions from ad hoc measures into institutionalized tools of collective security. President Woodrow Wilson championed economic isolation as a “peaceful, silent, deadly remedy” superior to military force. Inspired by Allied blockades that contributed to civilian starvation in Central Europe, the League of Nations incorporated sanctions into its Covenant under Article 16 in 1919. This marked the birth of multilateral sanctions, designed to enforce peace without bloodshed.

The interwar period tested this innovation. In 1921, the League threatened sanctions against Yugoslavia during a border dispute with Albania, prompting a swift resolution—a rare success. However, the 1935 Italian invasion of Ethiopia exposed flaws: partial sanctions on Italy failed to halt aggression, emboldening fascists and undermining the League’s credibility. Analytically, this era demonstrated that sanctions’ effectiveness hinges on unity among enforcers; divisions among great powers often render them symbolic.

World War II reinforced sanctions’ wartime role. The Allies’ blockade strategies echoed WWI, while post-war planning led to the United Nations’ Charter in 1945, empowering the Security Council under Article 41 to impose non-military measures.

The Cold War bifurcated sanction use: the U.S.-led CoCom embargo restricted technology exports to the Soviet bloc, aiming to maintain strategic superiority. Iconic cases included the U.S. embargo on Cuba from 1960, which persists today, and sanctions against apartheid South Africa in the 1980s. These highlighted sanctions’ dual role in ideological confrontations, often prolonging rather than resolving conflicts.

Post-Cold War Era: Proliferation and “Smart” Sanctions

The end of the Cold War in 1991 unleashed a surge in sanctions, with the UN Security Council authorizing them frequently against rogue states and non-state actors. Comprehensive sanctions on Iraq (1990–2003) following its invasion of Kuwait aimed to disarm Saddam Hussein but caused immense humanitarian suffering, with estimates of over 500,000 child deaths due to shortages. This backlash prompted a shift toward “targeted” or “smart” sanctions post-9/11, focusing on individuals, elites, or sectors to minimize civilian harm.

The U.S. emerged as the preeminent sanctioner, imposing over nine times more sanctions between 2000 and 2021 than in prior decades. Cases like Iran (nuclear program), North Korea (weapons proliferation), and Russia (post-2014 Crimea annexation and 2022 Ukraine invasion) illustrate this trend. Sanctions on Russia, involving asset freezes and SWIFT exclusions, disrupted global energy markets but failed to deter military action swiftly.

Analytically, modern sanctions leverage financial globalization—the dominance of the U.S. dollar and institutions like SWIFT—amplifying their reach but also risking backlash, such as de-dollarization efforts by targeted nations.

Effectiveness remains debated. A study of over 200 episodes from WWI to the early 2000s found sanctions successful in about 34% of cases, particularly for modest goals like policy tweaks rather than regime change. Success factors include multilateral cooperation, clear demands, and economic asymmetry favoring the sanctioner. Failures often stem from evasion (e.g., smuggling), adaptation by targets, or unintended alliances (e.g., Russia-China ties).

Humanitarian and Ethical Dimensions

A critical analysis must address sanctions’ dark side: their disproportionate impact on civilians. Interwar blockades caused mass starvation, setting a precedent for “man-made” deaths as the leading civilian killer between the world wars. In Iraq and Yugoslavia, broad sanctions exacerbated poverty and health crises, prompting ethical critiques. Smart sanctions aim to mitigate this by targeting elites—e.g., travel bans on Russian oligarchs—but leakage persists, as elites often shield themselves while populations suffer.

Politically incorrect yet substantiated: sanctions can entrench regimes by fostering nationalist backlash, as seen in Cuba and Iran, where embargoes bolstered anti-Western rhetoric. Moreover, they reflect power imbalances, with Western nations dominating imposition, raising questions of hypocrisy—e.g., U.S. sanctions on adversaries while overlooking allies’ violations.

Lessons for the Future

The history of sanctions is one of adaptation from ancient trade bans to sophisticated financial tools, reflecting humanity’s quest for non-violent coercion. Yet, their record is mixed: effective in niche scenarios but often prolonging suffering or escalating conflicts. As global interdependence grows, sanctions’ potency increases, but so do risks of economic fragmentation. In 2026, amid ongoing tensions with Russia, China, and Iran, policymakers must weigh efficacy against ethics, prioritizing multilateralism and humanitarian safeguards. Ultimately, sanctions are no panacea; true resolution demands diplomacy, not isolation.

SPONSORED CONTENT