Once celebrated as the defining freedom of modern life, sex and intimacy is quietly losing its central place in culture. From changing values to digital distractions and rising anxiety, a generational shift is underway—revealing that the age of sexual liberation may have been a brief historical interlude, not a permanent destination.

This article is based on a piece written by Dmitry Samoilov and published by RT. It was originally published in the online newspaper Gazeta.ru and subsequently translated and edited by the RT team.

Here’s the thing: the world many of us grew up in has vanished. And not because of wars, pandemics, or political upheavals—though all those matters. It has vanished because of sex.

No, this is not a personal confession. It is an observation about culture. Sex, once treated as a central axis of modern life, is quietly retreating. Not disappearing entirely, of course, but losing its former status as a defining experience, a marker of adulthood, a universal aspiration. And the scale of this retreat tells us something uncomfortable about where society has gone—and perhaps where it is going next.

In the 1990s, when sex was everywhere. Not just in private lives, but in public space. Advertising worked on the simple formula that sex sells. Some products logically lent themselves to erotic imagery; others did not. Yet a sexualized female body could be used to sell almost anything, including a bottle of mineral water. Newspapers, car magazines, and even publications devoted to mysticism or the paranormal routinely carried nude photo shoots.

Television, long before late-night hours, included bedroom scenes as part of normal programming. Youth series revolved around the anticipation of the first sexual experience. Schools distributed brochures about contraception. Words once whispered behind closed doors were now spoken on air: orgasm, masturbation, intercourse.

The message was unambiguous. Sex was not only normal; it was valuable, exciting, and culturally endorsed. It was treated as a permanent feature of modern life, a sign that society had matured, liberalized, and left behind repression and hypocrisy.

Thirty years later, we are told—almost casually—that sex is overrated.

This is not a matter of individual preference or generational prudishness. It is a structural shift. Surveys increasingly confirm what casual observation already suggests. Research by the NAFI analytical center shows that around 22 percent of people aged 18 to 25 are not sexually active. More than half of respondents report problems in their intimate lives. Forty percent say they cannot discuss sexual issues openly with their partner. Large numbers describe dissatisfaction, lack of desire, anxiety, or pain. Among women, these figures are especially stark.

Even more revealing are value rankings. Among people in long-term relationships, sex consistently appears at the bottom of the list of what is necessary for well-being. For many young respondents, it does not appear as a value at all. Health, income, career stability, travel, emotional balance, and personal freedom now dominate. Sex has slipped off the agenda.

This shift should not surprise us. The intimate sphere has become heavily problematized. Sex today competes with an entire digital universe that did not exist thirty years ago: short videos, streaming platforms, games, social networks, and algorithmically optimized content designed to capture attention with minimal effort. Why invest emotional and physical energy in a relationship—negotiating desires, boundaries, misunderstandings—when easier forms of stimulation are available on demand?

For a generation raised on the promise that sex was essential to happiness and self-expression, the retreat from intimacy is striking. Surveys now suggest not repression, but disengagement—an erosion of desire shaped by anxiety, choice overload, and a culture that treats intimacy as risk rather than reward.

Modern lifestyles exacerbate this competition. In an era of hustle culture, self-optimization, and endless productivity hacks, people prioritize routines centered on fitness regimens, meal prepping, mindfulness apps, and side gigs. These habits demand time and discipline, leaving little room for spontaneity.

The rise of wellness trends—intermittent fasting, biohacking, or high-intensity workouts—often emphasizes physical and mental peak performance, but at the cost of relational downtime. Sex, which requires vulnerability and presence, clashes with lifestyles built around control and efficiency.

To this we must add anxiety. Choosing a partner increasingly feels like navigating a minefield of red flags. Fear of manipulation, emotional abuse, trauma, power imbalance, and psychological labels has entered everyday language. Dating culture has absorbed therapeutic discourse, legal caution, and moral scrutiny. What was once spontaneous now feels like a risk assessment.

Then come practical considerations. What if sex leads to attachment? Commitment? Marriage? Children? A mortgage? In a world of precarious employment, expensive housing, and uncertain futures, even intimacy can feel like a liability. Withdrawal begins to look not like failure, but like rational self-defense.

Work-life balance disruptions play a pivotal role here. The boundaries between professional and personal spheres have blurred, especially post-pandemic with remote work and always-on digital tools. Long hours, constant emails, and the pressure to be perpetually available erode the energy needed for intimacy.

Shift workers, gig economy participants, and those in high-stress jobs often return home exhausted, opting for quick dopamine hits from scrolling or binge-watching over cultivating physical connection.

This imbalance not only drains physical stamina but also heightens stress levels, which directly impact libido and relational harmony. For many, the mental load of juggling career ambitions with household demands leaves sex as an afterthought, further straining partnerships and perpetuating cycles of disconnection.

So how did we get here?

The period we remember as sexually liberated may, in fact, have been a historical exception. Roughly from the 1950s onward, a unique constellation of factors aligned. Reliable contraception became widely available. Living standards rose. Housing conditions improved. Urbanization increased privacy. Education expanded. Sexual behavior gradually separated from reproduction and marriage. Demographers refer to this as the second demographic transition.

For the first time in history, large numbers of people could have sex primarily for pleasure, rather than obligation. Sex became decoupled from survival and embedded in self-expression. It could be discussed, represented, experimented with. The cultural emphasis on fulfillment, authenticity, and emotional compatibility reinforced this shift.

For a few decades, sex was not merely accessible—it was celebrated. We assumed this was a permanent achievement of modernity, an irreversible step forward.

Across most of human history, sex was not a sphere of personal discovery. For the majority of people, it was tied to necessity: reproduction, duty, social expectation.

Hygiene, privacy, and physical comfort—the conditions that make mutual pleasure possible—were luxuries. Concepts such as female orgasm, sexual compatibility, or consent as an ongoing negotiation were not central to everyday life. They belonged to philosophy, poetry, or elite culture, not mass experience.

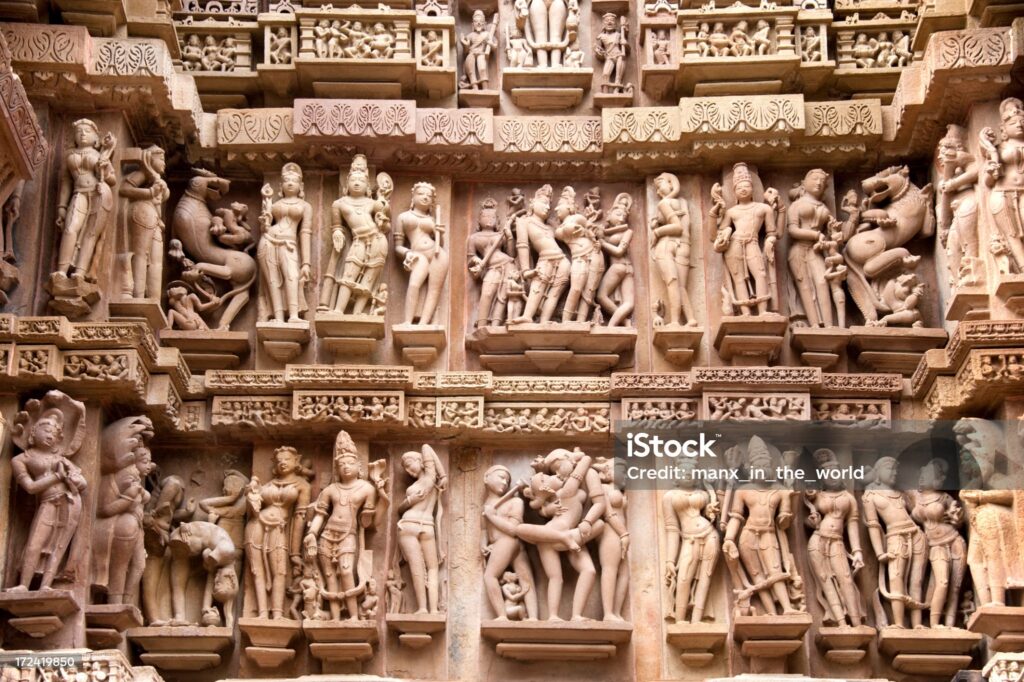

We like to point to ancient erotic art or texts such as the Kama Sutra as evidence that sex has always been sophisticated and liberated. But these artifacts represent symbolic or aristocratic worlds, not the lived reality of most people. What the late twentieth century did—briefly—was place sex at the center of mass culture.

That moment appears to be passing.

Today, sex competes not only with digital entertainment, but with a broader ideology of individual optimization. Time is treated as a scarce resource. Energy must be carefully allocated. People are encouraged to invest in career advancement, physical fitness, mental health, travel, and personal branding. Sex, with its unpredictability and emotional exposure, often appears inefficient.

It is messy. It disrupts routines. It creates obligations and vulnerabilities that do not fit neatly into productivity frameworks. In a culture obsessed with control, sex can feel like a loss of it. Lifestyle choices, such as minimalist living or digital nomadism, further prioritize mobility and independence over deep-rooted relationships, making sustained intimacy a logistical challenge.

The sexual freedom of the late twentieth century was never timeless. It emerged from rare social conditions—privacy, prosperity, contraception, and optimism—and may already be receding. What once felt like the natural endpoint of progress now appears as a fleeting moment in cultural history.

The result is a paradox. A society that was saturated with sexual imagery only a generation ago is producing cohorts less interested in sexual practice. The language of desire remains everywhere—in advertising, fashion, pop music—but lived reality increasingly reflects disengagement. Sex is talked about more than ever, yet practiced with less enthusiasm and frequency.

Some see this as a crisis. Others interpret it as liberation from pressure. Perhaps it is neither. Perhaps it is a rebalancing.

Sex may be returning to its place as one aspect of life rather than its organizing principle. The idea that youth must revolve around sexual conquest or experimentation now feels dated. Emotional safety, autonomy, and stability carry greater weight. In this reading, the decline of sex is not a symptom of decay but of recalibration, allowing space for more balanced lifestyles that integrate work, self-care, and meaningful connections without the disruptions of unchecked desire.

Still, the contrast with the 1990s is sharp enough to feel like a rupture. That earlier era left behind a vast archive of films, novels, music, and collective memories depicting a world in which sex seemed easy, central, and almost guaranteed. Intimacy appeared to be a shared cultural script rather than a personal negotiation fraught with risk.

Future generations may study that period the way we study other brief cultural phases: through art, nostalgia, and documentation rather than lived experience. The age of sexual confidence may come to resemble the age of disco or the era of grand ideologies—intense, influential, and ultimately temporary.

From Ancient to Modern

Looked at across the long arc of history, the age when sex was treated as a universal value now seems less like a destination and more like a passing season. For most of human time, sex belonged to necessity and order—to lineage, ritual, and survival—rarely to pleasure as a right or intimacy as a pursuit. Then, briefly, it was freed from those constraints and lifted into the center of modern life, celebrated as expression, promise, and proof of progress. That moment is fading. We are living through its quiet correction. Whether this retreat gives rise to deeper, more deliberate forms of intimacy, or settles into a longer era of distance and restraint, remains unknown. What is clear is that the sexual revolution, once imagined as the final chapter of liberation, now reads like a chapter itself—vivid, disruptive, and finite.

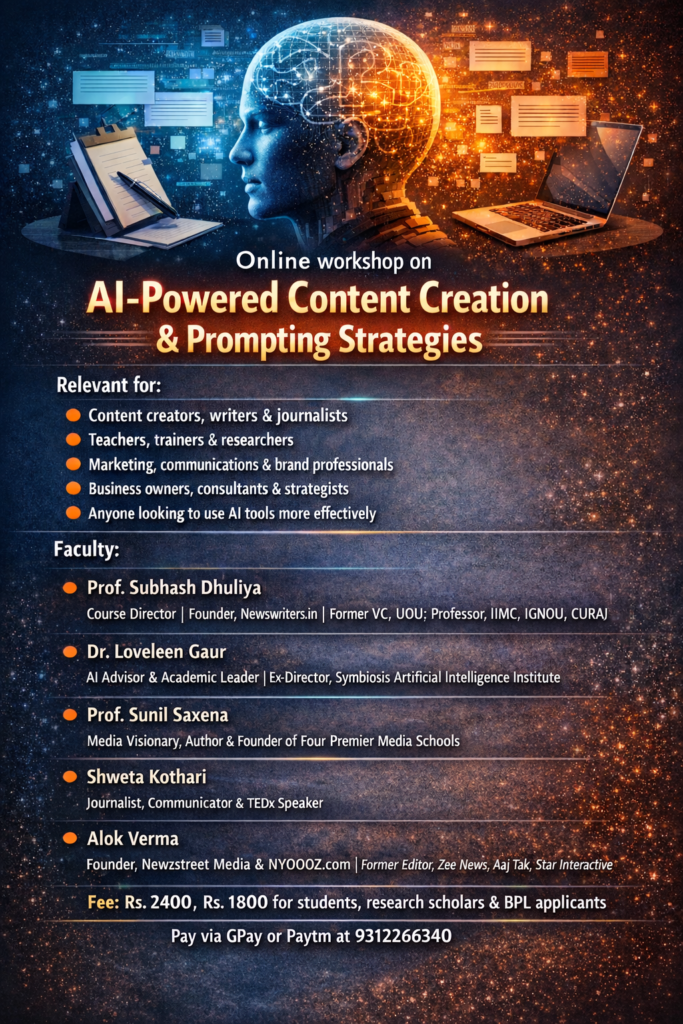

PROMOTIONAL CONTENT