Despite decades of awareness, the myth that women can prevent harassment or sexual violence through “modest” dressing or restricted mobility continues to surface in public discourse—especially in India, where political and social commentary still frames women’s clothing and curfews as safety measures. While overt victim-blaming has declined in Western leadership due to feminist movements like #MeToo, subtler forms persist in media narratives, legal scrutiny, and social attitudes. Rooted in patriarchal control and psychological biases, this rhetoric shifts responsibility from perpetrators to women, ignoring evidence that violence occurs regardless of attire or timing. True safety lies not in policing women’s behavior, but in accountability, consent education, and collective responsibility.

By Arti Singh

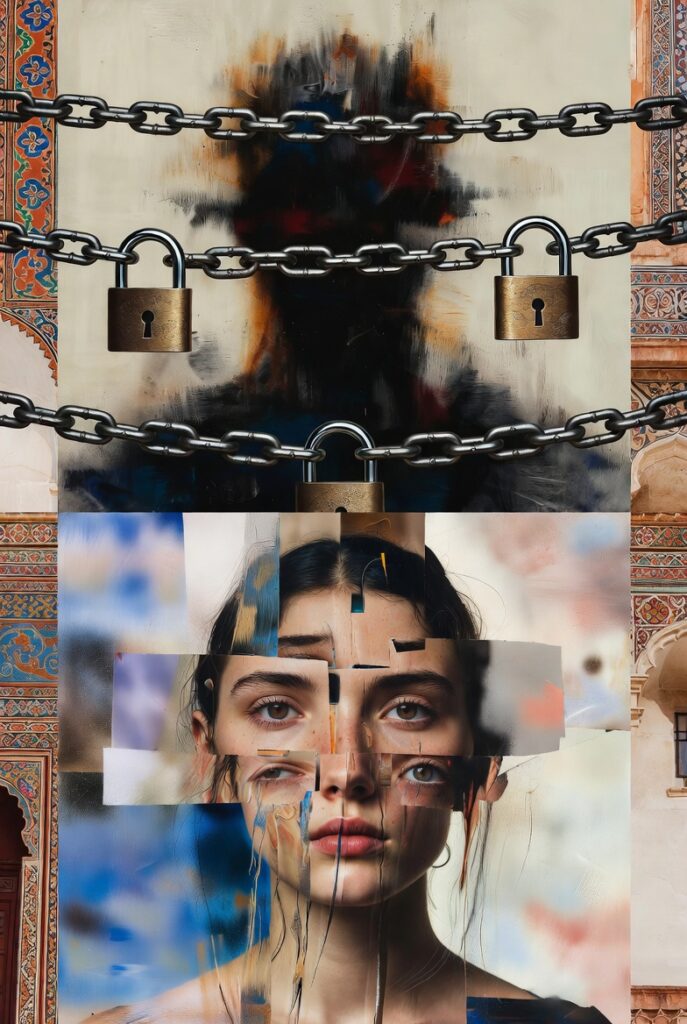

Across societies worldwide, conversations on sexual harassment, molestation, and sexual assault frequently drift into troubling territory. A familiar refrain suggests that women can avoid such crimes by modifying their behavior—by dressing “properly,” often coded as modesty, or by limiting their mobility after dark. This narrative, rooted in victim-blaming, subtly but powerfully shifts responsibility away from perpetrators and onto those who experience violence, revealing deeper social attitudes about gender, control, and accountability.

In societies across the globe, discussions around sexual harassment, molestation, and assault often veer into controversial territory. A recurring theme is the suggestion that women can prevent such crimes by altering their behavior—dressing “properly” (often implying modestly) or avoiding staying out late at night.

This narrative, rooted in victim-blaming, shifts responsibility from perpetrators to victims. Notable examples include Indian politicians like former Haryana Chief Minister Manohar Lal Khattar, who in 2015 remarked that if girls dressed decently, boys wouldn’t look at them wrongly, and Karnataka Home Minister G. Parameshwara, who in 2017 attributed Bengaluru’s New Year’s Eve molestations to women’s “Western” dressing. Even late Sheila Dikshit, Delhi’s former Chief Minister, in 2008 called journalist Soumya Vishwanathan “too adventurous” for being out alone at 3 a.m., implying late-night outings invite danger.

While such statements are less overt in the West today—due to movements like #MeToo—historical echoes persist, such as a 2011 Toronto police officer’s advice for women to avoid “dressing like sluts.”

From a sociological viewpoint, victim-blaming is a manifestation of patriarchal structures that reinforce gender norms and power imbalances. Sociology posits that societies are organized around systems of dominance, where men historically hold authority over women’s bodies and behaviors. In patriarchal cultures, women’s autonomy is often curtailed under the guise of protection, framing harassment as a consequence of deviance from traditional roles.

For instance, in India, where collectivist values emphasize family honor and female modesty. Sociologist Raewyn Connell’s theory of hegemonic masculinity explains this: dominant ideals of manhood encourage control over women, while femininity is idealized as submissive and modest. When women “transgress”—by wearing modern attire or venturing out at night—they are seen as inviting violation, absolving societal failures in law enforcement and education.

In the West, overt victim-blaming by political leaders has declined since the 2010s, but subtler forms persist in media and legal systems. U.S. court cases, for instance, often scrutinize victims’ clothing or alcohol use, as noted in Susan Ehrlich’s research on rape trials—reflecting what Martha Burt called “rape myth acceptance” and contributing to chronic underreporting of assaults. Sociologically, victim-blaming acts as social control. From a Durkheimian perspective, it reinforces dominant norms by discouraging “deviant” behavior, preserving the status quo rather than addressing the roots of gendered violence

This phenomenon is amplified by intersectionality, a concept coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, which highlights how gender intersects with class, caste, and ethnicity. In lower socioeconomic strata, women face heightened scrutiny; a working-class woman out late might be blamed more harshly than her affluent counterpart.

Globally, sociological studies, such as those from the World Health Organization, show that victim-blaming correlates with high gender inequality indices.

In the West, while overt political statements are rare post-2010s due to feminist backlash, subtle forms persist in media and legal systems. For example, U.S. court cases often scrutinize victims’ clothing or alcohol consumption, as analyzed in Susan Ehrlich’s sociolinguistic research on rape trials. This “rape myth acceptance” (per Martha Burt’s 1980 scale) normalizes blame, reducing reporting rates—only 23% of U.S. assaults are reported, per RAINN data.

Sociologically, victim-blaming also serves as a mechanism of social control. Émile Durkheim’s functionalism suggests it maintains order by reinforcing norms; blaming victims discourages “deviant” behavior, preserving the status quo.

In conservative societies, this ties into moral panic, where media amplifies isolated incidents to justify restrictions on women. India’s post-Nirbhaya (2012 Delhi gang rape) discourse saw officials emphasizing curfews over systemic reforms, diverting attention from inadequate policing. Comparative sociology reveals contrasts: Scandinavian countries, with high gender equality, exhibit lower victim-blaming, as per European Union surveys.

Here, policies focus on perpetrator accountability, not victim conduct. Yet, even in progressive contexts, globalization spreads these ideas; social media echoes Indian politicians’ views in Western anti-feminist circles, blending cultural relativism with backlash against #MeToo.

Shifting to psychological perspectives, victim-blaming stems from cognitive biases and emotional defenses that help individuals cope with threats. Melvin Lerner’s “just world hypothesis” (1980) is central: people believe the world is fair, so bad outcomes must be deserved. When confronted with molestation, observers blame victims’ dress or timing to restore this illusion, avoiding the discomfort of randomness.

This bias is stronger in ambiguous cases; if a woman is out late in “revealing” clothes, it’s easier to attribute fault to her than acknowledge societal dangers. Experiments, like those by Ronnie Janoff-Bulman, show participants rate victims as more culpable if their behavior seems controllable—e.g., “she shouldn’t have been out alone.”

Victim-blaming—through prescriptions on “proper” dress or curfews—is not a harmless opinion but a reflection of entrenched patriarchy and psychological denial. It harms survivors, weakens justice, and perpetuates inequality. Challenging it demands accountability-driven policies, education to dismantle bias, and cultural shifts toward empathy. Until then, such rhetoric—whether in India or as lingering Western relics—underscores how far societies must go. True safety comes not from restricting women, but from building systems that protect everyone

Psychologically, this also involves attribution errors. Fritz Heider’s attribution theory distinguishes internal (dispositional) vs. external (situational) causes. Victim-blamers favor internal attributions: “She dressed provocatively” (her fault) over “The perpetrator is aggressive” (societal issue). This is exacerbated by empathy gaps; men, less likely to experience harassment, underestimate risks, per studies in Psychology of Women Quarterly. Ingroup biases play a role too—people blame outgroup victims more, as seen in caste-based assaults in India or racial disparities in U.S. cases.

From a developmental angle, psychologists like Carol Gilligan highlight how gender socialization shapes these views. Girls learn to self-regulate for safety, internalizing blame, while boys are taught entitlement. This leads to secondary victimization: survivors experience shame, reducing help-seeking. Cognitive dissonance theory (Leon Festinger) explains perpetrators’ and enablers’ rationalizations; officials like Parameshwara might blame victims to avoid admitting governance failures.

Trauma psychology adds depth: blaming eases collective anxiety but harms mental health. PTSD rates among blamed survivors are higher, per APA research, fostering isolation and depression.

Interweaving these perspectives reveals a feedback loop. Sociologically enabled norms feed psychological biases, perpetuating cycles. For example, in India, colonial legacies blended with indigenous patriarchy amplify modesty mandates, psychologically internalized as self-protection.

In the West, individualism clashes with collective feminist gains, but biases linger in subconscious judgments. Recent data from 2023 UN Women reports show 37% globally believe women in revealing clothes “ask for it,” down from 50% in 2010 but still prevalent.

Critics argue victim-blaming ignores evidence: assaults occur regardless of attire or time, as per FBI and NCRB statistics—many happen daytime, in homes, by acquaintances. Psychologically, interventions like bias training reduce just-world beliefs; sociologically, education reforms challenge norms. Movements like SlutWalk (sparked by the Toronto incident) blend activism with awareness, shifting narratives.

In conclusion, victim-blaming—exemplified by advice on “proper” dress and curfews—is not mere opinion but a symptom of deeper sociological patriarchy and psychological defenses. It harms survivors, deters justice, and sustains inequality. Addressing it requires multifaceted approaches: policy reforms for accountability, education to dismantle biases, and cultural shifts toward empathy. Until then, such statements, whether from Indian leaders or Western relics, remind us of the work ahead. True safety lies not in restricting women but in empowering societies to protect all.

About the Author

Arti Singh is an experienced journalist and an alumna of the India Today Media Institute. She has worked with leading television news channels, including Aaj Tak and ABP News, across diverse editorial and production roles. She also headed the PR team at the US-based company GirishGPO, gaining valuable experience at the intersection of media, communications, and corporate strategy. With hands-on expertise in newsroom operations, reporting, and content development, she brings a strong understanding of broadcast journalism and contemporary media practices. A committed feminist, her work reflects a sustained interest in gender equity and women’s rights.